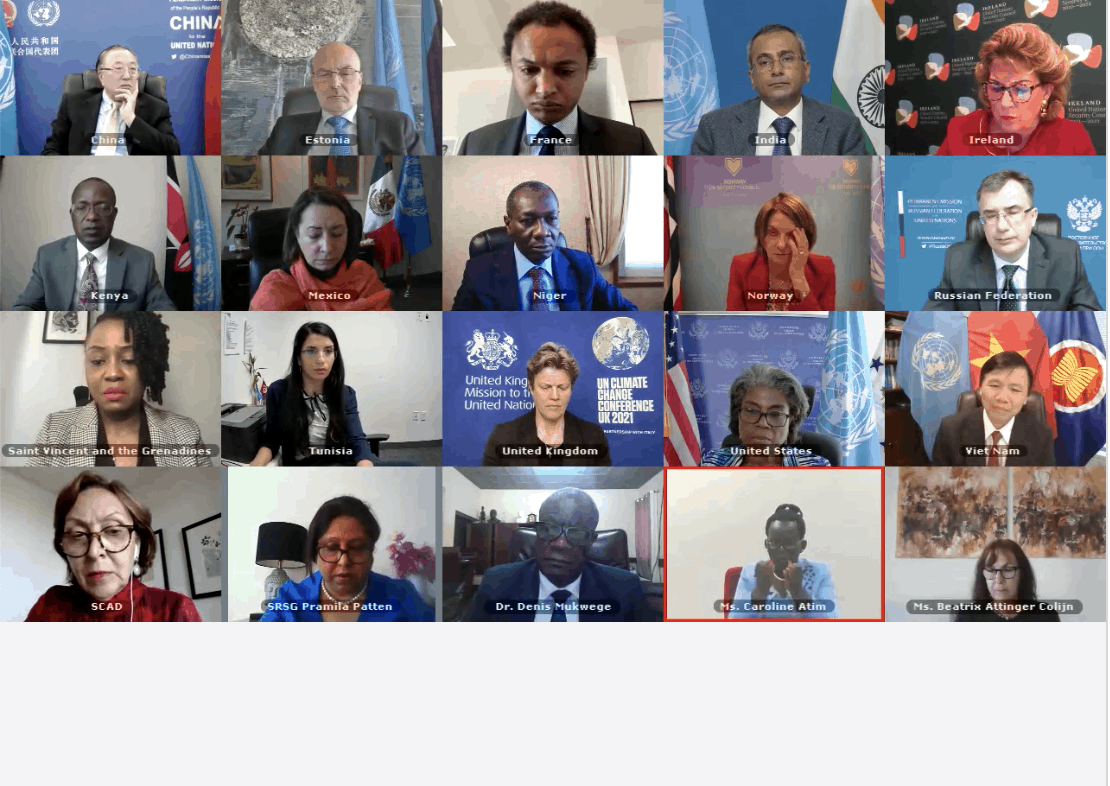

Mr. President, Excellencies, civil society colleagues, ladies and gentlemen,

Thank you for the opportunity to deliver this statement on behalf of the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. I am Caroline Atim, Founder and Executive Director of the South Sudan Women with Disabilities Network, an organization that works directly with women with disabilities, including survivors of gender-based violence (GBV). Today, I speak on behalf of these survivors, as well as women and girls with disabilities, as I am a deaf woman. My sign language interpreter will be voicing my statement today.

Despite the peace deal, South Sudan remains engulfed by intercommunal, ethnic, political and armed conflicts, where GBV is deliberately used as a tool of humiliation against women and girls.[1] More than 65% of South Sudanese women have experienced sexual or physical violence, a figure that is double the global average and among the highest in the world.[2] Women and girls with disabilities are at even greater risk of sexual violence during conflict.[3]

A lethal combination of impunity[4] for perpetrators and deep-rooted inequality[5] and discrimination means that GBV, including sexual violence against women and girls, is not taken seriously as a crime, nor is its devastating impact addressed. Even before the current conflict, rape in marriage was considered acceptable,[6] and more than 50% of girls married[7] before they turned 18. Rates of child, early and forced marriage have only increased since the conflict began, and have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] Survivors are often forced to marry their rapists.[9] Girls are sometimes raped to compensate for crimes of their relatives or as acts of revenge.[10] Women have been raped and forced to bear children to replace dead relatives.[11] These inhuman and unjust practices must end.

Mr. President,

Globally, women and girls with disabilities are 2-3 times more likely to experience GBV, abuse and exploitation, [12] especially during conflict, as they face increasing isolation, lose access to support networks, may have limited mobility or are left behind.[13]

Let me share the example of a young girl whose heartbreaking story illustrates the plight of women and girls with disabilities. In 2014, during the conflict in Bor, a deaf 14-year-old girl was raped several times after being abandoned by family members who fled the fighting. She was unable to communicate her trauma to anyone or seek necessary health and other services in the immediate aftermath. When I met her, and was able to communicate with her in Sign Language, we were able to understand what happened to her and provide her with immediate care — only to find out that she was HIV positive. Had she had access to an interpreter and timely medical care, she could have been helped sooner. But these necessary services were not available to her, and she had to suffer in silence. This is unacceptable.

This story illustrates some of the ways in which the suffering of women and girls with disabilities is compounded by the discrimination they already face.[14] They are easy prey for rapists, who know they can act with impunity because women with disabilities, even more than others, may not be believed if they report this violence. They often struggle to access limited or otherwise inadequate health facilities, safe shelters or even basic health and legal information when they need them most.[15] The COVID-19 pandemic has made these conditions even worse due to lockdowns and interruption of services, which have kept women with disabilities isolated in their homes.[16]

And yet, responses to GBV often neglect the specific needs of women and girls with disabilities and very limited data is systematically collected about our experiences, including by the UN.[17] Instead, there is a lack of understanding of our rights, combined with stereotypes that we cannot make choices for ourselves and that our perspectives do not matter. For example, the false assumption that women with disabilities are not capable of having consensual relationships means many are never provided with information about their bodies or their rights, in turn making them more vulnerable to abuse, unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.[18]

In situations where survivors of sexual violence bear children, both the children and the women who bear or raise them can face devastating consequences due to deep-rooted gender inequality. They are both targets of extreme stigma and discrimination.[19] These women are often ostracized by their communities and abandoned, leaving them with few resources, and can face long-lasting physical and psychological trauma.[20] Some are forced out on the streets while others, especially girls, are traded off for cattle. The only way to address the tragedy of these women and girls and their children is to address prevailing inequalities and protect their fundamental rights in areas of conflict.[21]

The rights, experiences and voices of survivors must be at the center of any response to GBV. This includes survivors with disabilities.[22] Survivors have fundamental rights that entitle them to services according to their specific needs — they must have access to comprehensive, accessible and non-discriminatory services, including psychosocial support, sexual and reproductive health and rights, mental health care, access to legal services and training to develop livelihood skills. This is what a robust survivor-centered approach looks like — and this is the standard to which this Security Council committed itself in resolution 2467 (2019).

Currently, the widespread availability of firearms in our highly militarized society leaves women at risk of all forms of GBV.[23] The sale of illicit weapons must be stopped to ensure women’s safety. Those responsible for crimes must be held accountable through the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, which should be established and fully functional in accordance with Chapter 5 of the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS).[24] All parties must prioritize the full, equal and meaningful participation and leadership of women in all of their diversity, including those with disabilities,[25] in all aspects of the current peace process, and ensure that the 35% quota provided for in the R-ARCSS is met. South Sudan must respect its human rights obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and all relevant UN Security Council resolutions, including resolution 2475 (2019) on protection of people with disabilities in armed conflicts, and all resolutions on Women, Peace and Security.[26] Lastly, Mr. President, we urge all actors to ensure that rights, inclusion and accessibility for women and girls with disabilities are at the heart of all efforts to prevent and respond to GBV.[27]

Mr. President,

For the sake of our humanity, our dignity, our future, we need an end to war and violence in South Sudan. The lives of thousands of South Sudanese women and girls, in Juba, in Malakal, in Bentiu, in Wau and Jonglei, cannot be traded away for a fleeting respite from fighting. If their suffering is forgotten, our wounds will never heal. This risks future conflict. For sustainable peace, we need inclusivity, justice and reconciliation with the past.

In conclusion, I urge the Security Council to:

- Reinforce that a holistic survivor-centered approach is, by definition, one that is rights-based, accessible and designed in partnership with diverse women, including women with disabilities, and urge all governments to uphold their obligations to provide services for GBV, including sexual and reproductive health services. In accordance with Resolution 2567 (2021), all parties to the conflict and other armed actors must cease and prevent further sexual violence, and adopt a survivor-centered approach in their response in South Sudan.[28] Additionally, the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) must fulfill its protection mandate to prevent, and respond to GBV wherever it is deployed, and strengthen the capacity of the justice system to fully prosecute all forms of GBV and human rights violations.

- Emphasize that justice and accountability efforts, including compensation and reparations processes, must be rights-based, survivor-centered, inclusive and non-discriminatory, and above all, they must avoid exacerbating the harm already done. Those responsible for crimes must be held accountable through the Hybrid Court for South Sudan, which should be established and fully functional in accordance with Chapter 5 of the R-ARCSS.

- Urgently stem the flow of illicit weapons in order to establish an environment conducive to implementation of the R-ARCSS.

- Call on all actors to ensure that the rights and participation of, and accessibility for, women and girls with disabilities are at the heart of efforts to prevent and respond to GBV. Prioritize implementation of Resolution 2475 (2019) in order to ensure the rights and perspectives of women and girls with disabilities are reflected across all country-specific agenda items, including by mandating peace operations to take into account women and girls with disabilities in protection of civilians and human rights monitoring activities, and to support their full, equal and meaningful participation in peace, political and humanitarian processes.

- Demand all parties prioritize the full, equal and meaningful participation and leadership of women in all of their diversity, including those with disabilities, in all aspects of the current peace process. This includes meeting the 35% quota provided for in the R-ARCSS for women’s participation at all levels.

- Call on the international donor community to adequately resource civil society organizations led by women and girls, particularly those with expertise in disability rights, so they can take on leadership roles throughout the humanitarian-development-peace continuum.

The Security Council can and must fulfill its obligations to the people of South Sudan, and to the many women and girls in conflicts around the world to whom it committed to ending, once and for all, all forms of GBV.

Thank you.

[1] CARE International, ‘The Girl Has No Rights’: Gender-Based Violence in South Sudan, May 2014, https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/media/k2/attachments/CARE_The_Girl_Has_No_Rights_GBV_in_South_Sudan.pdf.

[2] International Rescue Committee, No Safe Place: A Lifetime of Violence for Conflict-Affected Women and Girls in South Sudan, 2017, https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/2294/southsudanlgsummaryreportonline.pdf.

Ellsberg M, Ovince J, Murphy M, Blackwell A, Reddy D, Stennes J, et al. (2020) No safe place: Prevalence and correlates of violence against conflict-affected women and girls in South Sudan. PLoS ONE 15(10): e0237965. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237965.

[3] Women Enabled International, Rights of Women and Girls with Disabilities in Conflict and Humanitarian Emergencies, https://womenenabled.org/pdfs/Women%20Enabled%20International%20-%20Rights%20of%20Women%20and%20Girls%20with%20Disabilities%20in%20Conflict%20and%20Humanitarian%20Emergencies%20-%20English.pdf.

[4] Human Rights Council, Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan (A/HRC/46/53), 4 February 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session46/Documents/A_HRC_46_53.pdf.

[5] UNMISS, OHCHR, Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Northern Unity, 15 February 2019, https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/SS/UNMISS_OHCHR_report_CRSV_northern_Unity_SouthSudan.docx&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1618407764109000&usg=AOvVaw1eGU5s6Yt09NYpTQKkmrNf.

[6] Human Rights Watch, “This Old Man Can Feed Us, You Will Marry Him” Child and Forced Marriage in South Sudan, 7 March 2013, https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/03/07/old-man-can-feed-us-you-will-marry-him/child-and-forced-marriage-south-sudan.

[7] Girls Not Brides, Atlas – South Sudan, https://atlas.girlsnotbrides.org/map/south-sudan/.

[8] Oxfam, ‘Born to be Married’: Addressing Early and Forced Marriage in Nyal, South Sudan, February 2019, https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620620/rr-born-to-be-married-efm-south-sudan-180219-en.pdf.

Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Committee on the Rights of the Child’s Review of South Sudan, 30 November 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/30/submission-committee-rights-childs-review-south-sudan.

Conciliation Resources, South Sudan Democratic Engagement, Monitoring and Observation Programme, Fighting sexual and gender-based violence: rape as an issue in South Sudan, March 2019, https://rc-services-assets.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/Fighting_sexual_and_gender-based_violence_2019_WEB.pdf.

Human Rights Council, Detailed findings of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan (A/HRC/46/CRP.2), 18 February 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session46/Documents/A_HRC_46_CRP_2.pdf.

[9] Human Rights Watch, “This Old Man Can Feed Us, You Will Marry Him” Child and Forced Marriage in South Sudan.

[10] International Rescue Committee, No Safe Place: A Lifetime of Violence for Conflict-Affected Women and Girls in South Sudan.

[11] Kane, S., Kok, M., Rial, M. et al. Social norms and family planning decisions in South Sudan. BMC Public Health 16, 1183 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3839-6.

[12] Women Enabled International, The Right of Women and Girls with Disabilities to be Free from Gender-Based Violence.

[13] Women Enabled International, UNFPA, Women and Young Persons with Disabilities, Guidelines for Providing Rights-Based and Gender-Responsive Services to Address Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights, November 2018, https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA-WEI_Guidelines_Disability_GBV_SRHR_FINAL_19-11-18_0.pdf.

Women’s Refugee Commission, International Rescue Committee, Building Capacity for Disability Inclusion in Gender-Based Violence Programming in Humanitarian Settings, June 2015, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/GBV-disability-Toolkit-all-in-one-book.pdf.

Women’s Refugee Commission, Disability Inclusion: Translating Policy into Practice in Humanitarian Action, March 2014, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Disability%20Inclusion_Translating%20Policy%20into%20Practice%20in%20Humanitarian%20Action.pdf.

Handicap International, Disability in humanitarian context: Views from affected people and field organisations, July 2015, https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/handicapinternational/pages/1500/attachments/original/1449158243/Disability_in_humanitarian_context_2015_Study_Advocacy.pdf?1449158243.

[14] Women Enabled International, The Right of Women and Girls with Disabilities to be Free from Gender-Based Violence.

[15] Human Rights Watch, South Sudan: People with Disabilities, Older People Face Danger, 31 May 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/05/31/south-sudan-people-disabilities-older-people-face-danger.

UNMISS, Survivors of Sexual Violence in South Sudan Struggle to Access Health Care, 19 May 2020, https://unmiss.unmissions.org/survivors-sexual-violence-south-sudan-struggle-access-health-care.

UNMISS, OHCHR, Access to Health for Survivors of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in South Sudan, May 2020, https://unmiss.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/access_to_health_for_survivors_of_conflict-related_sexual_violence_in_south_sudan.pdf.

[16] Women Enabled International, COVID-19 at the Intersection of Gender and Disability: Findings of a Global Human Rights Survey, May 2020, https://womenenabled.org/pdfs/Women%20Enabled%20International%20COVID-19%20at%20the%20Intersection%20of%20Gender%20and%20Disability%20May%202020%20Final.pdf.

[17] Women Enabled International, UNFPA, Women and Young Persons with Disabilities, Guidelines for Providing Rights-Based and Gender-Responsive Services to Address Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.

Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women with Disabilities, paras. 34, 41-45, U.N. Doc. A/67/27 (2012).

Karen Hughes, Mark A Bellis, Lisa Jones, Sara Wood, Geoff Bates, Lindsay Eckley, Ellie McCoy, Christopher Mikton, Tom Shakespeare, & Alana Officer, Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, 379 THE LANCET 1621, 1626-28 (Feb. 28, 2012).

[18] Women Enabled International, UNFPA, Women and Young Persons with Disabilities, Guidelines for Providing Rights-Based and Gender-Responsive Services to Address Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.

Women Enabled International, The Right of Women and Girls with Disabilities to be Free from Gender-Based Violence.

[19] Joanne Neenan (LSE), Closing the Protection Gap for Children Born of War, 2018, https://www.lse.ac.uk/women-peace-security/assets/documents/2018/LSE-WPS-Children-Born-of-War.pdf.

[20] Tanya Birkbeck, The Globe and Mail, Children of War: Carrying on with babies born of rape, 28 November 2017, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/in-south-sudan-mothers-and-their-children-born-of-rape-become-forgotten-victims-ofwar/article37118719/.

[21] Global Justice Center, The Right to an Abortion for Girls and Women Raped in Armed Conflict: States’ positive obligations to provide non-discriminatory medical care under the Geneva Conventions, February 2011, https://globaljusticecenter.net/documents/LegalBrief.RightToAnAbortion.February2011.pdf.

[22] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health and rights for all women, in particular women with disabilities, 29 August 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/CRPD/Statements/GuaranteeingSexualReproductiveHealth.DOCX.

[23] UNDP, National Small Arms Assessment in South Sudan, https://www.undp.org/content/dam/southsudan/library/Reports/South%20Sudan%20National%20Small%20Arms%20Assessment%20-%20Web%20Version.pdf.

Human Rights Council, Assessment mission by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to improve human rights, accountability, reconciliation and capacity in South Sudan: detailed findings (A/HRC/31/CRP.6), 10 March 2016

https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session31/Documents/A-HRC-31-CRP-6_en.doc.

[24] IGAD, Signed Revitalized Agreement On The Resolution Of The Conflict In South Sudan, 12 September 2018, https://igad.int/programs/115-south-sudan-office/1950-signed-revitalized-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-south-sudan.

[25] Women Enabled International, Submission on the Rights of Women with Disabilities in the World of Work to the Working Group on the issue of Discrimination against Women in Law and in Practice, 30 August 2019, https://womenenabled.org/pdfs/WEI%20Submission%20Women%20with%20Disabilities%20and%20the%20World%20of%20Work%20August%2030,%202019.pdf.

[26] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health and rights for all women, in particular women with disabilities.

OHCHR, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 18 December 1979, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cedaw.aspx.

[27] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health and rights for all women, in particular women with disabilities.

[28] UN Security Council, Resolution 2567 (S/RES/2567), 2021, https://undocs.org/en/S/RES/2567(2021).