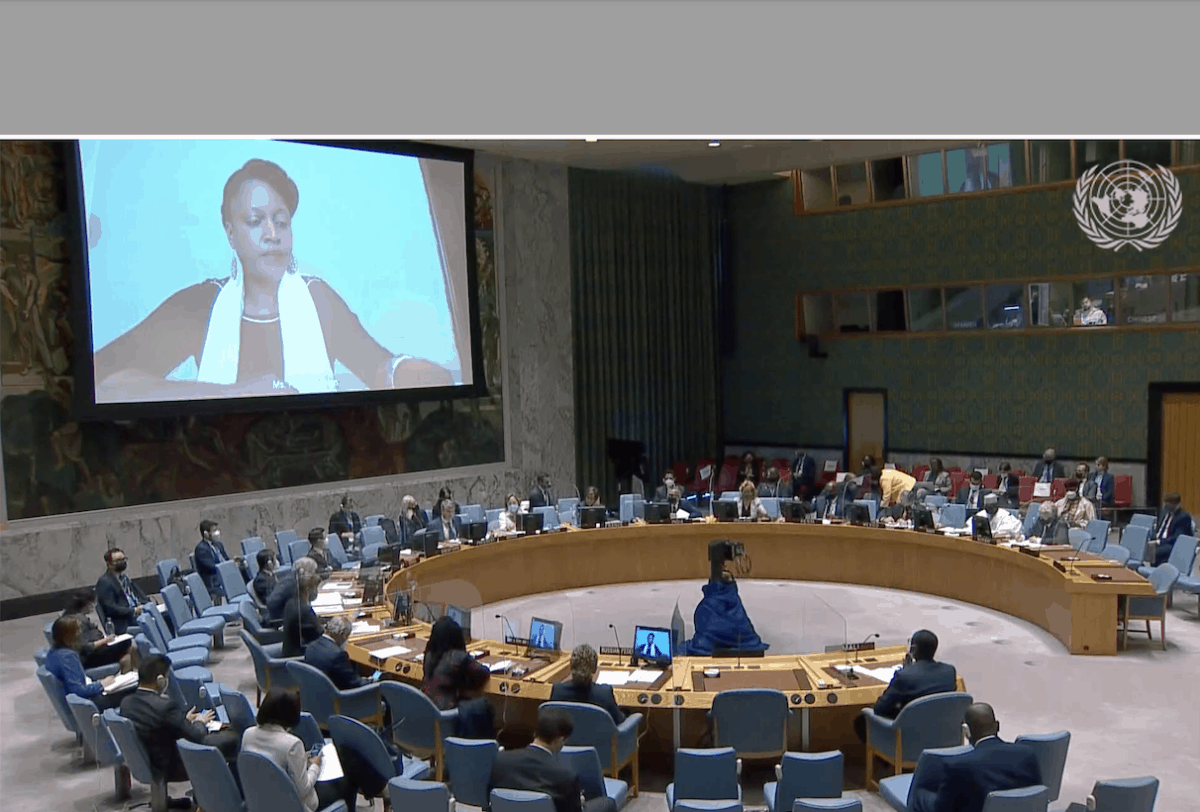

I would like to begin by thanking you, Mr. President, for giving me this opportunity to brief the Security Council on the situation in Mali and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. I am Fatima Maiga, president of a coalition of women from the signatory groups of the Peace Agreement and director of the consulting firm ESEN, which has notably piloted the process of integrating women into the Monitoring Committee of the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation (APR) in Mali on behalf of the Norwegian Embassy.

Excellencies, Members of the Security Council,

The realization of the WPS agenda in Mali remains dependent on strong political will and relative political and institutional stability. Unfortunately, the fifth post-coup transition in Mali in sixty years of independence, two of which have taken place under the current MINUSMA mandate, shows us the long way to go to stabilize Mali, in accordance with the Mission’s primary objectives. It also shows that without a more significant treatment of the root causes of the multifaceted crisis that has shaken the country since 2012, the vicious circle of instability will continue: these include the issues of inclusive and equitable governance of land and productive resources and access to justice.

Ladies and gentlemen, my speech will focus on two points with recommendations:

- The observation of a marked deterioration in women’s rights before and during the current transition

- The priorities and challenges of the current Transition in relation to the WPS agenda and their implications for MINUSMA’s mandate

Regarding Point 1: The 2020-2021 mandate of MINUSMA has been marked by a strong trend of closing the space for women’s rights in Mali, despite notable progress. As part of this progress, nine women from the signatory parties are now members of the Monitoring Committee (CSA in French) of the APR for the first time in six years.[1] Norway is to be congratulated for its pivotal role in achieving this result.

However, the overall situation of women’s rights in Mali remains critical:

- 2.9 million women and girls are in need of emergency humanitarian assistance.[2]

- In areas under the partial control of armed groups — estimated today as covering about two thirds of the territory — and sometimes under local agreements between these groups and the besieged populations, hundreds of thousands of girls and women are today deprived of access to schools, health centers, markets or fields. In addition, too many of them continue to suffer sexual violence, including gang rape and sexual slavery, with impunity for the perpetrators and without knowledge of or access to the still too few holistic care services: in 23% of recorded cases, survivors cannot access health care and 48% of the health centers are not equipped with forensic kits for rape cases. [3]

- The judicial treatment of the 115 cases of conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence (GBV) committed since 2012-2013, i.e. almost a decade ago, has not seen any progress to date;[4]

- The repeated violations of Law 052 (gender law) in all the governments put in place since its promulgation in 2018 and in a more pronounced manner, during the hundred or so high-level appointments made by the transitional authorities from September 2020 to the present day;

- The suspension in 2020 by the transitional government of the draft law against GBV, under pressure from religious groups.

Regarding point 2: The Security Council and MINUSMA have a key role to play in putting the issue of gender and the implementation of resolution 1325 (2000) back at the heart of the transition’s priorities; indeed, eight of the twelve months of MINUSMA’s new mandate will take place during the new phase of the Transition, which has set as a priority the holding of free and credible elections by February 2022, as well as ensuring the security, stabilization and protection of people throughout the country. It should be noted that gender issues, in particular the prevention and management of sexual violence and GBV, were not included among the six priorities of the initial roadmap of the Transition. The expected process of adjusting these priorities for the remaining nine months of the transition must therefore be used to try to strengthen their inclusive nature both from the point of view of stakeholders and of geographical and thematic coverage. This can only be done if there is a real break with the ‘wait-and-see’ attitude that has largely prevailed over the last nine months regarding the WPS agenda, despite being backed by a robust National Action Plan for the implementation of Resolution 1325. In particular, the WPS agenda must move from being just everybody’s business to being a clearly defined responsibility submitted to the assessment of certain key stakeholders. Therefore, it is recommended that the Security Council:

- Broaden the political and operational mandate of MINUSMA beyond the RPA to include current reconciliation and peace efforts through political dialogue and negotiations with armed groups including those designated as “terrorist” in central Mali; this is in line with the recommendations of the 2020 Inclusive National Dialogue, which were reaffirmed in the Transition Roadmap.

- Urgently strengthen the institutional gender mechanism and the means of action of women’s civil society organizations to enable them to monitor and influence the course of the two priorities outlined above. A new mechanism entirely dedicated to strengthening the transition, electoral and negotiation processes by optimally taking into account gender equality issues could be envisaged;

- Urgently support the transitional authorities in affirming and respecting: Mali’s national and international commitments, particularly in terms of the representation of women in nominative and elective positions; humanitarian law and human rights, including in the context of negotiations with armed groups; in this area, the provisions of Resolution 1325 calling for the effective involvement of women in these processes must be reaffirmed and applied;

- Give priority in the new MINUSMA mandate to a tightened WPS agenda with precise indicators, particularly on the issue of the judicial treatment of cases of conflict-related sexual violence and GBV, and the holistic care of survivors of such violence.

Mr. President and Excellencies members of the Security Council, it goes without saying that the people of Mali are in desperate need of peace and prosperity after nearly a decade of violent conflict and recurrent instability. These aspirations will only become a reality if women’s rights are protected and they are truly involved in building a lasting peace. I appeal to you, the members of the Security Council, for your support.

Thank you.

[1] MINUSMA, Journée Internationale des Femmes: leadership, paix et réconciliation en temps de COVID-19, 8 March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/mali/journ-e-internationale-des-femmes-leadership-paix-et-r-conciliation-en-temps-de-covid-19.

[2] OCHA, Aperçu des Besoins Humanitaire Mali, February 2021, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/documents/files/mli_hno_2021_mali_v4.pdf.

[3] United Nations Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-related sexual violence (S/2021/312), 30 March 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/S_2021_312_E.pdf.

[4] Ibid.