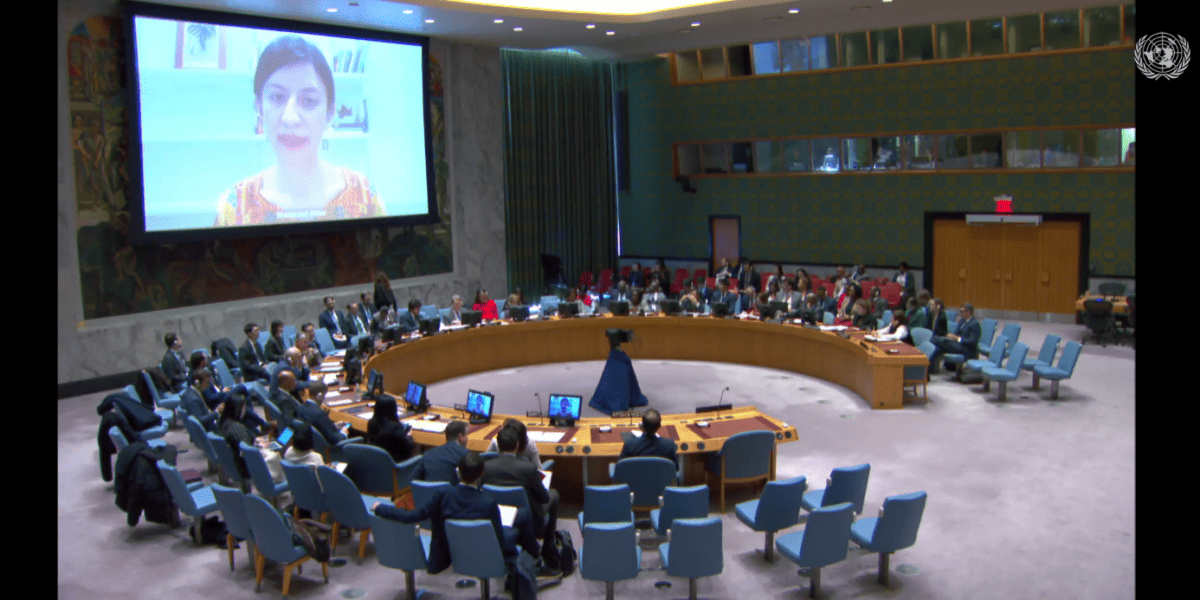

This statement was made by Ms. Shaharzad Akbar, Executive Director of Rawadari, at the United Nations Security Council Meeting on Afghanistan on 20 December.

Excellencies,

Thank you for this opportunity to brief you.

My name is Shaharzad Akbar. I am a human rights defender and Executive Director of Rawadari, an Afghan civil society organization that has reported on the situation of human rights, including of women, girls and marginalized groups, since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021.

Today, I want to share with you the trends we have observed on the ground in Afghanistan, what this tells us about the Taliban’s vision for the country, and most importantly, what this means for international engagement, including by the Security Council, going forward.

Since the Taliban’s return to power, we have documented an alarming pattern of human rights violations, across the board.

We have witnessed repression of women’s rights in every conceivable sphere of life, from education, to work, to movement, to participation in public life—repression so widespread and systematic that international experts have deemed it gender apartheid.[1] Daily, we witness more cohesive enforcement of these restrictions with the rise in public corporal punishments and an increasing number of decrees limiting women’s rights and freedoms, now numbering 90.[2] The Taliban’s promises of an inclusive government, respect for women’s rights, or that any of these restrictions were temporary, have proved to be a lie.

We have witnessed a brutal crackdown on civic space, on freedom of expression and the media, and on human rights defenders. The Afghanistan Journalists Center has reported 99 incidents of violations of press freedom in 2023, including 41 arrests and criminal charges of journalists.[3] At least two women human rights defenders, Manizha Sediqi and Parisa Azada, who were targeted for their activism, remain in custody.[4]

Despite the declared “general amnesty,” the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and civil society organizations like ours have documented the ongoing killings of former security forces and government employees, which, to date, have not been investigated.[5]

We have witnessed targeted attacks, forced displacement and marginalization of Afghanistan’s various religious and ethnic groups such as Hazaras, Uzbeks, Turkmens and Tajiks, who have no meaningful representation in the de facto administration.[6] The Taliban have further excluded Shia religious scholars from provincial Ulema councils.[7]

Further, we have witnessed the dismantling of an independent judiciary and the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, undermining of the independence of other legal institutions such as the Afghanistan Independent Bar Association, and replacement of women, Shia and other non-Taliban judges and legal professionals, which has resulted in widespread impunity and undermined the rule of law.[8]

What do these trends tell us?

The pattern of violations that I have just described illustrate the Taliban’s destructive vision for my country’s future.

In this vision, there is no rule of law.

In this vision, there are no dissenters, no human rights defenders and no independent media.

In this world, there is no quality and comprehensive education, and as a result, no economic prosperity.

There are no ballot boxes or respect for the people’s right to choose.

In this future, Afghanistan’s government is almost entirely composed of madrassa-educated Taliban members with an unquestioning loyalty to their leader. Women and marginalized ethnic, linguistic and religious groups have no share in power and decision-making.

In this vision, women are less human than men. Women’s education does not matter. Their rightful place is in the home. They have no role in decision-making and governance. They are constantly surveilled and held in place by their own male children and relatives, taxi drivers, the religious police, and the entire machinery of the de facto authorities. When they face violence and abuse, their only options are to bear it or die.

Excellencies, I ask you: is this a future the international community is willing to support?

Now, let me share with you a different vision. We—the majority of Afghans—want an equal, peaceful and prosperous country. We want a country that is not at war with its women and girls. We want a country that embraces its rich ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity. And we want a country that respects the human rights of all Afghans.

The Taliban have shown you, the international community, who they are. And we, Afghan women, have told you what we want.

The choice before you is—will you support our vision of a peaceful, equal, diverse, democratic Afghanistan, or the Taliban’s vision, one that violates the UN Charter, and the fundamental values that this Council claims to uphold?

Right now, it is the Taliban who are defining the rules of the game, and humanitarian organizations, the UN and the international community are forced to play by their rules in order to negotiate modest concessions. It is ironic that while we have insisted that humanitarian aid can never be conditional, it is the Taliban who have imposed conditions on the work of the UN and humanitarian organizations by banning Afghan women from working in most sectors. And, regrettably, the UN and humanitarian actors have complied.

Let me be clear: Afghanistan needs continued and increased international assistance. We should also continue to explore ways to relieve the economic pressure on ordinary Afghans without benefiting the Taliban. However, the situation in Afghanistan is not merely a humanitarian crisis. It is a political, security, and most fundamentally, a human rights crisis—and we need you, the Security Council, to be clear that human rights, especially women’s rights, will be central to the international community’s next steps in Afghanistan.

I therefore leave you with the following recommendations.

First, as you deliberate on how to take forward the recommendations made by the independent assessment on Afghanistan mandated by Resolution 2679, it is critical to note that no steps should contradict the repeated recommendations of many Afghan women that there can be no unprincipled engagement with or recognition of the Taliban, or a seat for them at the UN, as long as their systematic discrimination against women and girls continues. Setting out a roadmap for engagement as the Taliban’s abuses deepen sends a message that women’s rights are dispensable. For this reason, I urge you not to provide a blanket endorsement of the report’s recommendations without establishing clear and explicit safeguards to protect the human rights of Afghan women, including their full, equal, meaningful and safe participation, in any decision-making or new mechanisms, such as creation of a UN Special Envoy or broader UN-convened meetings of Special Envoys, going forward. I urge you to be clear that “normalization” of relations with the Taliban is not possible without swiftly reversing all restrictions on women’s rights, which you called for in Resolution 2681, and meeting Afghanistan’s obligations under international law, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).[9] This must be a collective red line for Member States, UN agencies and all humanitarian actors, and central to discussions of any other areas regarding Afghanistan, including security, the economy, development, counter-terrorism, narcotics and migration. It is also critical that any next steps do not fall below what the Security Council has already called for.

Second. I urge you to support all avenues to ensure justice and accountability for human rights violations by the Taliban, including by bringing a case against Afghanistan before the International Court of Justice for violations of CEDAW and through the establishment of an independent international accountability mechanism on Afghanistan.

Third. I urge Member States and other relevant UN bodies to label and investigate the Taliban’s treatment of Afghan women as both gender persecution and gender apartheid. Further, include gender apartheid in the Crimes Against Humanity treaty currently under consideration.

Fourth. It is critical that UNAMA, as the primary UN presence in the country, retain and implement its current mandate in full, especially monitoring and advocating for respect for human rights, and providing protection for those at risk.

Finally, the international community must prioritize support to Afghan human rights defenders and civil society, both those who have been forced into exile, as well as the brave activists who remain in the country, by expediting resettlement for those at risk, funding civic work in Afghanistan, and continuing to meaningfully consult with the diverse human rights community of Afghanistan.

Thank you.

[1] Karima Bennoune, “The International Obligation to Counter Gender Apartheid in Afghanistan,” Columbia Human Rights Law Review 54, no. 1, 2022: 1-88. https://hrlr.law.columbia.edu/hrlr/the-international-obligation-to-counter-gender-apartheid-in-afghanistan/.

[2] UNAMA, “Corporal Punishment and the Death Penalty in Afghanistan,” May 2023, https://unama.unmissions.org/corporal-punishment-and-death-penalty-afghanistan.

United States Institute of Peace, “Tracking the Taliban’s (Mis)Treatment of Women,” accessed September 18, 2023, https://www.usip.org/tracking-talibans-mistreatment-women.

[3] Afghanistan Journalists Center, “Press Freedom Violations 2023,” 2023, https://afjc.media/db/en/report/2023.

[4] Amnesty International, “Afghanistan: Stop punishing women protestors,” 7 December 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa11/7509/2023/en/.

[5] UNAMA, “Impunity prevails for human rights violations against former government officials and armed force members,” 22 August 2023, https://unama.unmissions.org/impunity-prevails-human-rights-violations-against-former-government-officials-and-armed-force.

Rawadari, “Human Rights Situation in Afghanistan: Mid-year Report 1 January to 30 June 2023,” August 2023, https://rawadari.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/RW_AFGHumanRights2023_English.pdf?#.

[6] Rawadari, “Repression, Regressions & Reversals: One Year of Taliban Rule & Human Rights in Afghanistan, 15 August 2021 – 15 August 2022,” 10 December 2022, https://rawadari.org/10122022196.htm/.

[7] Report of the Secretary-General, “The Situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security,” (S/2023/941), 1 December 2023, https://unama.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/sg_report_on_the_situation_in_afghanstian_december_2023.pdf.

[8] Rawadari, “Repression, Regressions & Reversals.”

[9] United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2681 (S/RES2681), 27 April 2023, https://undocs.org/S/RES/2681(2023).