This policy brief outlines the findings from the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security’s (NGOWG) monitoring and analysis of the United Nations (UN) Security Council’s daily work over the course of 2017.

The overall aim of the policy brief is to assess the implementation of the women, peace, and security (WPS) policy framework in the work of the Security Council. The analysis and recommendations build on our well-established policy guidance project, the Monthly Action Points (MAP) on Women, Peace and Security, as well as broader advocacy over the course of 2017.[1]

Over the last 18 years, the eight resolutions adopted by the Security Council on WPS have formed a strong foundation for the operationalization of the WPS agenda by the UN system and Member States, resulting in, at a rhetorical level, an acknowledgment of these issues as important. The WPS agenda recognizes that conflict has gendered impacts, and that women have critical roles to play in peace and security processes and institutions. Taken holistically, this agenda recognizes that a gender-blind understanding of conflict significantly undermines international peace and security efforts. Women, peace and security is, therefore, not only a principle but a call to action for Member States, the Security Council and the UN system.

Outside the Security Council, there are a range of policy developments that mutually reinforce the WPS agenda: the Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons (A/CONF.229/2017/8), the Arms Trade Treaty (A/RES/67/234); the sustainable development goals (SDGs), including Goals 5 and 16 (A/RES/70/1); the sustaining peace initiative (S/RES/2282 (2016), A/RES/70/262); and the three peace and security reviews of 2015 (A/70/357; A/69/968); Global Study on 1325).

One, particularly concerning development over the past year, was the significant cuts to the budgets for peace operations. These cuts directly impacted one of the earliest institutional structures established within the UN system to support the implementation of the WPS agenda in peace operations: gender units and Gender Advisors. Cuts were made to all peacekeeping mission budgets across the board, impacting human rights monitoring, protection of civilians, gender, and child protection capacity. However, the cuts have had a particularly acute impact on the gender functions of each mission, both in terms of the number of positions, as well as a concurrent loss of seniority. The loss in seniority of several Gender Advisor positions, contrary to the recommendations from the 2015 peace and security reviews, will result in the marginalization of gender in senior decision-making processes within peacekeeping missions.[2] Additionally, the development and launch of the System-wide Strategy on Gender Parity, unfortunately, has at times been co-opted to argue that loss of gender expertise within missions will be less impactful when there are more women working in the mission. This is a false presumption: all women are not gender experts who are able to provide strategic advice on how to ensure the needs and priorities of local women in conflict and crisis-affected countries are identified and addressed.

Positively, over the last year, we have seen an increase in formal engagement between the Council and civil society representatives, in line with resolution 2242 (2015), resulting in the invitation of civil society representatives, including from women’s organizations, to brief during country-specific meetings. In 2016, only one such briefing took place, but in 2017 nine civil society representatives (eight women) were invited to brief the Security Council during country-specific meetings in addition to the two civil society speakers at the two annual WPS open debates.[3] The eight women leaders shared the experiences of women and girls in Nigeria, Afghanistan, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), South Sudan, and Yemen, and provided concrete recommendations on ways forward for the international community.[4] These country-specific briefings continue to be contested and on occasion politically challenging, but the progress made in 2017 will significantly contribute to their institutionalization in 2018 and beyond.

In 2017, the Council’s implementation of WPS agenda continued to move in a positive direction and there has been progress in several areas: there has been an increase in attention to WPS in the Security Council’s response to crises, for example; and there were some new provisions in the mandates of peacekeeping operations that call for women’s participation in security processes, including disarmament; and the Security Council has improved its inclusion of recommendations on WPS in reports. Yet, despite these improvements, the challenges and ongoing gaps in implementation mean the promise of the WPS agenda is not yet realized.

- Women’s participation must be at the heart of the implementation of the women, peace and security agenda including through recognition of women’s agency and the vital roles played by women in local communities and inclusion of women in political and peace processes and institution-building.

- The structures supporting the implementation of the WPS agenda within the UN system and the Security Council must have adequate capacity, expertise, and funding.

- All conflict analysis must be gendered and intersectional, taking into account masculinities, femininities, gender roles, age, diverse sexual orientations and gender identities, expressions and sex characteristics (SOGIESC) and be associated with sex and age-disaggregated statistics.

- Civil society, including women’s groups, must be recognized as crucial contributors to international peace and security and to sustaining peace. Promoting the spaces for their meaningful participation, as well as the rights of women human rights defenders should be a priority.

- Prevention should be at the heart of peace and security policymaking. A preventive approach should be transformative and breaks down artificial silos, implements international human rights and humanitarian law, and better reflects the reality and complexity of peace and security, particularly the gendered dimensions of all stages of conflict.

- Effective humanitarian assistance and distribution of aid require an appreciation of the different impact conflict can have on women, men, girls, boys, and individuals with diverse SOGIESC, to ensure that humanitarian actors provide the most appropriate response.

- Huge gaps remain in the area of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR), as well as security and justice sector reform (SSR) despite multiple, previous resolutions adopted by the Security Council emphasizing the importance of gender-sensitive DDR and SSR processes throughout planning, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation phases.

- Securing accountability for the crimes and human rights violations committed and ending the impunity of all perpetrators – state and non-state actors – is a paramount obligation. The widespread or systematic nature of the many crimes of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), including those committed before the outbreak of war, constitutes crimes against humanity and should be addressed as a matter of priority.

Methodology

The NGOWG is the only organization that monitors and analyzes the daily work of the Security Council to assess the implementation of the WPS agenda using an intersectional feminist lens.

The WPS policy framework, grounded in eight resolutions adopted by the Security Council, and referred to as the “women, peace and security agenda.” The WPS agenda recognizes that conflict has gendered impacts, that it affects women, girls, boys, and men, differently, and that women have critical roles to play in peace and security processes and institutions. It calls for the participation of women at all levels of decision-making in conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping and peacebuilding efforts; protection and promotion of women’s rights, including ensuring justice and accountability systems are gender-sensitive, the prevention SGBV, and provision of services for survivors; and adoption of gender perspectives in conflict prevention and resolution, peacebuilding, humanitarian responses and other processes. Taken holistically, this agenda recognizes that a gender-blind understanding of conflict significantly undermines international peace and security efforts.

Our work is informed by feminist approaches to international relations, which broadly recognize gender as a fluid and intersectional social construction that is a source of power between diverse women and men, femininities and masculinities; the causes and consequences of war cannot be understood without reference to gender and its intersection with other constructions. Thus, our feminist lens combined with the WPS framework provides us with a unique analytical framework to monitor and analyze the work of the Security Council.

Grounded in this framework, we analyze the “regular work” of the Security Council, which encompasses a reporting and decision-making cycle that provides several opportunities to assess the extent to which both the information and the decision-making is inclusive and responsive to WPS concerns; the yardstick against which we measure are the resolutions adopted by the Security Council itself over 18 years, including particularly the provisions in resolutions 2122 (2013) and 2242 (2015).

We utilize both qualitative and quantitative methods to analyze publicly available documents, primarily resolutions and presidential statements adopted by the Security Council, as well as reports of the Secretary-General submitted according to the Security Council’s request. Our analytical process provides a snapshot of both the information flowing into the Security Council, as well as the action is taken. The scope of our analysis encompasses any agenda item on which the Security Council has adopted an outcome document or considered a report of the Secretary-General.[5]

Our qualitative research utilizes a dataset that includes more than 500,000 data points and more than 100 variables which provide information on the connections and trends across all aspects of the WPS agenda within and between documents. With the provisions of the WPS agenda as a baseline, our feminist-informed methodology enables us to uncover additional dimensions and patterns in the Council’s work.

References to the WPS agenda are sentences which have one (or a variation) of relevant keywords (such as “women,” or “girl,”) in the body of a document. We assess the “quality” of the reference based on a range of variables and conditions, including whether or not the keyword occurred in the context of statistical information (i.e., identifying how many women were injured or impacted by violence), or is the subject of more extended analysis. Broadly, we value references that contain nuances and details about the gender-specific needs, concerns, and rights of women, or provide analysis about the gendered impacts of conflict on women, as such references can most tangibly inform the work of the Council in terms of the WPS agenda.

Overall Trends

Similar to previous years, the WPS agenda was inconsistently implemented and addressed in the work of the Security Council. There are few, if any, examples in which both the information received by the Security Council and the decisions adopted by the Security Council included holistic, balanced WPS references across the scope of the agenda; we consider this a reasonable test of WPS implementation.

Progress was seen in the context of certain types of decisions adopted by the Security Council and on specific thematic issues. However, the ad-hoc nature of these improvements can only lead to the conclusion that often progress was driven by individual Council members, rather than a deep understanding within the Security Council as a whole, of the way in which WPS should be central to the Security Council’s consideration of peace and security issues.

The most significant improvements in 2017 were in the context of the Security Council’s response to country-specific and regional crisis situations, such as the Lake Chad Basin region, as well as in resolutions adopted and reports considered on specific thematic issues, such as small arms and light weapons (SALW), trafficking, and counter-terrorism. Additionally, there were some positive developments regarding sanctions regimes and reporting by associated expert groups.

The ad-hoc and inconsistent integration of WPS is problematic because it suggests that WPS-related issues and activities are not being monitored, or even implemented consistently, which undermines and complicates efforts to promote accountability for meaningful WPS implementation. The inconsistent implementation can be illustrated by several trends we have identified over the past year, such as incongruent provision of information when compared to mandated reporting requirements; commitments in resolutions to supporting women’s participation that does not align with the bulk of the Council’s focus in terms of WPS; failure for recommendations in one Security Council subsidiary body to be reflected in the other conversations on the same country; and continued grouping of women and children or youth, resulting in an incomplete picture of the complex and diverse roles women have in conflict situations.

Although the Council has improved the breadth of WPS issues discussed, energy and attention is often focused primarily on discussing a narrow range of protection concerns, specifically prevention and response to SGBV, thus ignoring not only broader issues related to gender equality and women’s empowerment, but other critical aspects of women’s protection in, for example, humanitarian settings or addressing the specific protection needs of particular groups, such as adolescent girls or people with diverse SOGIESC.[6]

This narrow focus means that the Council is engaging primarily with the human rights violation and its immediate causes and consequences, rather than systematically engaging with the root causes of long-term structural violence, and, as a result implicitly reproducing gendered stereotypes of women in conflict as victims. Further, this invisibilizes men (and women) as actors who perpetuate structures and power dynamics that underpin gender inequality; men and boys as victims of violence; and completely ignores the experiences of persons of diverse SOGIESC.[7]

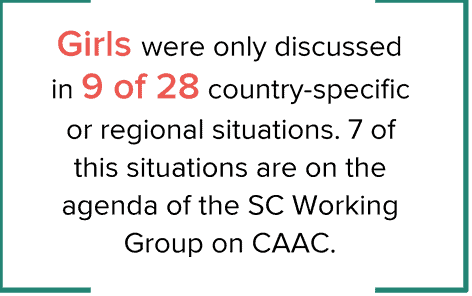

The Security Council overlooked the particular rights, concerns, and role of girls, adolescent girls, and young women in both country-specific and thematic agenda items.

In 2017, references to girls occurred in the context of nine country-specific and regional situations: Afghanistan, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, Liberia, Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan, and Nigeria and the Sahel. Notably, all but two of those countries have been discussed in the context of the thematic agenda item of children and armed conflict. This indicates that there is some amount of cross-pollination in terms of information flow; however, it also underlines that in most situations, issues related to girls are overlooked, unless raised in the separate context of the children and armed conflict (CAAC) agenda item. The majority of the relevant references were to “women and girls” as a group. The exception to this was specific references to girls in the context of targeted attacks against girls’ schools in Afghanistan and UN-efforts to support education for girls in Mali and the Sahel; details regarding human rights violations, including SGBV and other forms of exploitation, targeting girls in the DRC, Mali, Sudan, South Sudan; and recruitment of children for both combat and non-combat roles armed groups in South Sudan and Nigeria.

Only one mission has a mandate which explicitly references girls; the African Union mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is required to “ensure that women and girls are protected from sexual violence, including sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA).”[8] As noted above, more often than not, in reporting and resolutions, “girls” are subsumed into other categories of civilians. By using general categories – women, youth or children – age-related gender dimensions of the crisis are overlooked, resulting in an incomplete picture of the situation, and gaps concerning specific interventions.[9] Girls, adolescent girls, and young women face additional discrimination due to their age. Adolescent girls, for example, are often at increased risk of SGBV, exploitation, trafficking, and forced marriage, particularly when displaced.[10] Girls, as well as adolescent girls, are regularly targeted by armed groups for a range of purposes, including but not limited to recruitment as combatants or for sexual slavery; in some armed groups, young female fighters are empowered as leaders; thus reintegration efforts need to be both age and gender-responsive.[11]

It is clear that the Informal Expert Group (IEG) on WPS, established by the Security Council with the adoption of resolution 2242 (2015), plays a vital role in drawing attention to key WPS concerns, including those related to women’s participation and empowerment; however, due to a range of factors, including lack of universal participation, the conversation on the gender dimensions in specific conflict situations is only taking place in the IEG, and not in the Council as a whole. As a result, instead of complementing the Council, the IEG is supplementing it.

The overall impact of the IEG is difficult to measure; over the course of 2017, the Council adopted new language in resolutions on several country situations on the IEG’s agenda, reflecting some of its recommendations. It is fair to say that the IEG has contributed to strengthening the expertise and knowledge at the expert level for Council members on the gender dimensions of the country situations under discussion.

The co-chairs of the IEG play an important role in facilitating the meetings, encouraging the attendance of all Council members and ensuring the discussions are integrated into broader Security Council considerations as they relate to the region or country. The co-chairs have an opportunity to extend this leadership by ensuring senior mission and UN leaders also discuss the issues raised during IEG meetings as part of the formal Security Council consultations and hold leaders accountable for any gaps in implementation and reporting.

Further, the IEG has served as an excellent opportunity for civil society organizations to share information and recommendations, which is integrated into briefing materials. However, due to the lack of universal participation in the IEG, the conversations and outcomes can seem siloed and separate from the Council’s discussions on those country situations, particularly when the periodic reporting of the Secretary-General is weak on WPS concerns.[12]

Over the last few years, the mandates of most peace operations have been strengthened by the Security Council to contain multiple WPS provisions, often accompanied by requests for specific WPS reporting. Recent new language complements and expands on existing calls. While there have been overall improvements in mandates, what is apparent is that the Security Council and peace operations continue to struggle conceptually with specific core WPS issues, notably women’s participation, empowerment, and agency.

The vast majority of the direct references to “women’s empowerment” throughout reports of the Secretary-General are superficial, occurring in paragraphs that simply offer a rhetorical reference to the importance of promoting women’s empowerment or list women’s empowerment as one goal of an activity or process. Examples of good analysis exist, but with few exceptions, they are ad-hoc and a result of a particular confluence of lucky factors, rather than systematic attention to gender at every stage of planning and implementation. The Council must ensure that it not only discusses the impact of conflicts on women, but the agency women have in creating, affecting, ending, and eventually moving on from conflicts, and establish the expectation that the Council will not merely discuss women superficially, but engage in analyzing the disparate or familiar impacts of aspects of each and every conflict on both genders.

The Council continues to make decisions based on information which is mostly gender-blind.

There is often a gap in the information provided on the outcomes of mission activities working with and supporting women’s participation and empowerment, which results in an incomplete and insufficient understanding of the gender dimensions of the conflict and broader conflict dynamics. As a baseline, per the Council’s previous decisions, all reports should include information and analysis on the impact of armed conflict on women and girls, patterns and early warning indicators of the use of sexual violence, the gender dimensions, including the role of women, in all areas of conflict prevention and resolution, peacemaking and peacebuilding, details regarding measures taken to protect civilians, particularly women and girls, against sexual violence, as well as related recommendations.[13]

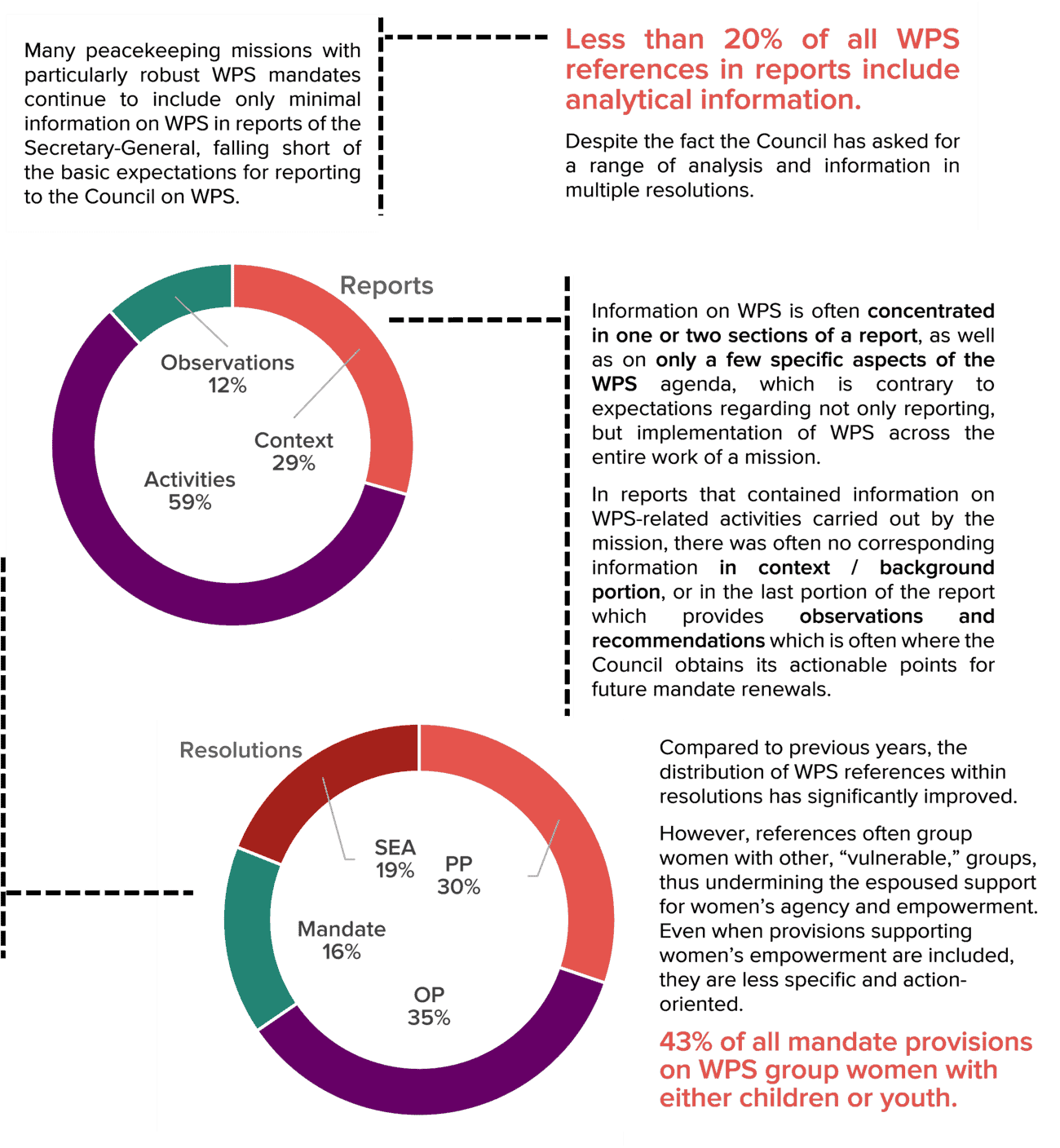

Based on our analysis, less than 20% of all reports contained any reference that could be considered analytical. Analytical references are primarily concentrated in reports of the Secretary-General on special political missions or in sanctions group reports. Holistic gender analysis must look at the broader relationships between gender and crisis, including how gender roles, norms, and identities are shaped by and shape conflict. Importantly, this must also take into account masculinities, femininities, patriarchy and militarism.[14] As was noted by the Secretary-General, to integrate gender into small arms control, there needs to be consideration of “masculinity and the need for power projection of young men.”[15] Importantly, there must be nuance in any analysis; it is not all masculinities that are problematic, and it is not only the particular harmful masculinities that are the structural problem but also the militarized contexts and the conditions of extreme socio-economic stress (coupled with the perseverance of patriarchal norms, upheld by men and women) that underpin this violence.

There was a noticeable increase in the inclusion of sex-disaggregated data; however, this increase was not complemented by an increase in the analysis of the data nor provision of information that is further disaggregated by age.

The Council has previously called for the “systematic collection, analysis and utilization of sex and age-disaggregated data (SADD) that is required to assess the specific needs and capacities of women, and to meaningfully measure to what extent recovery programmes are benefiting women, men, girls, and boys.”[16] However, the vast majority of the data was not sex and age-disaggregated as it only provided data on women and children.

In 2017, nearly 50% of all references to “women” and 70% of all references to “girls” in reports were in the context of statistical information. The data was primarily focused on human rights violations, attacks against civilians, beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance, attendees and participants in events, and troop or police deployment. While data is an essential component of the information and analysis that should be included in reporting to the Security Council, it is only a starting point in terms of integrating WPS analysis and considerations in the Council’s discussions, as well as facilitating better evidence-based decision-making.[17] Moreover, although data aids in revealing unseen disparities, inequalities, and the unpacking of the impact of conflict on women, it alone does not provide insight into how, why, and the ways in which women participate in activities organized by peace operations.[18]

There is a clear correlative relationship between mandates, gender expertise, and information and analysis on WPS.

Our analysis reveals that having a mandate to address WPS correlates with the almost universal inclusion of some information on WPS in reporting. As a result, it is clear that there is an ongoing need for the Security Council to explicitly include provisions in future mandates that call for WPS to be mainstreamed, in addition to component-specific provisions on women’s meaningful participation and women’s and girls’ protection including in DDR; SSR; rule of law (ROL); and protection and monitoring of human rights. The presence of Gender Advisors (GAs) and Women Protection Advisors (WPAs) results in more detailed information on the gender dynamics of situations as well as information on WPS activities carried out by the mission, indicating that their presence has an operational impact, as well as information gathering and analytical impact.

Our analysis further reveals a correlative relationship between the presence of GAs and an improvement in information on women’s participation and empowerment in reports of the Secretary-General. This relationship is most visible in reports on Department of Political Affairs (DPA)-led political missions, which often have stronger mandates to support women’s participation in elections and constitutional reform processes. The influence of WPAs is seen in the inclusion of information on SGBV: in fact, the rate of increase in references to SGBV and other protection issues aligns with the deployment of WPAs beginning in 2012. These missions had stronger and more detailed information on SGBV activities undertaken by the missions. This relationship is one of the main reasons why the NGOWG continues to advocate for the maintenance of all gender expertise in light of the recent budget cuts.[19]

It is important to note that the responsibility for implementing WPS provisions in mandates does not lay solely with GAs or WPAs; their presence should facilitate the implementation of those provisions and support training and capacity building. Mission leadership must support the GAs and WPAs as the ultimate responsibility for the mainstreaming of WPS must lie with the mission leadership as prescribed by resolution 2242 (2015).

Country-specific and regional situations

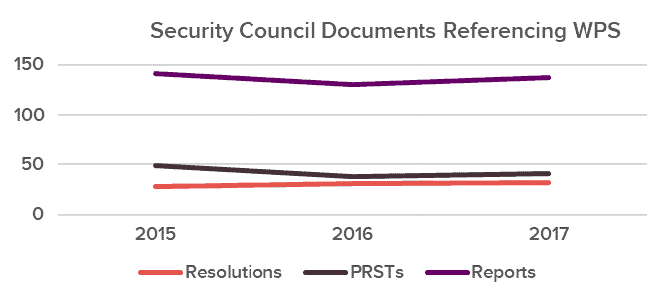

There were 28 country-specific or regional situations discussed by the Security Council in 2017.[20] Overall, the Security Council has broadly continued to include WPS references in country and region-specific resolutions and reports, relatively consistently. Compared to 2016, the Security Council significantly improved its inclusion of WPS in presidential statements and maintained or improved its inclusion of WPS in resolutions and reports.

Peace Operations

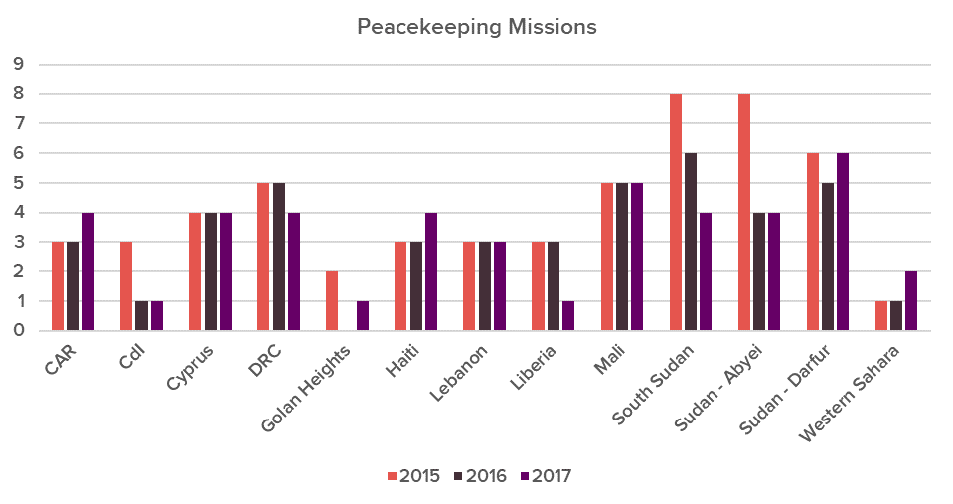

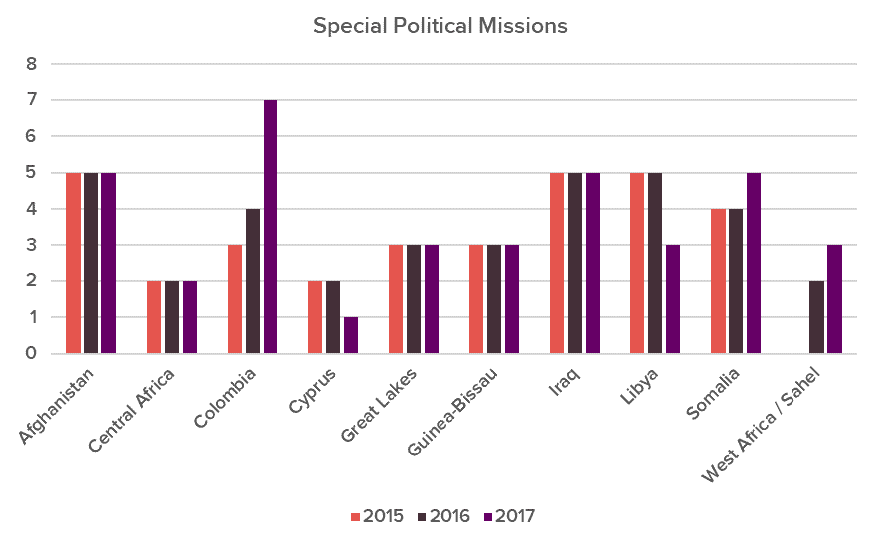

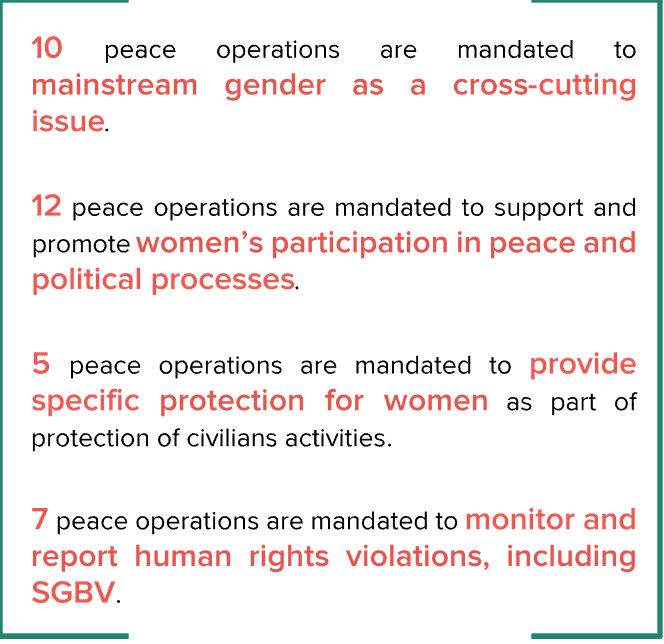

In 2017, the Security Council adopted resolutions, presidential statements, and/or received reports on 25 peace operations: 14 peacekeeping missions and 11 special political missions. Two missions that were active in all of or part of 2017 have since drawn down: Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire. Of all missions active in 2017, 17 of 25 peace operations had women, peace and security-related tasks explicitly articulated as part of their mandates: 9 peacekeeping missions and 8 special political missions.

A total of 12 peace operations were mandated to address women’s participation, empowerment, and gender equality in the context of elections, political processes, reconciliation and/or peace processes in 2017. Language in the mandates of the missions in Afghanistan, Haiti, Libya, Sudan (Darfur), West Africa and the Sahel was new or updated in 2017; the new language was mostly in the context of requesting the mission support the “participation, involvement and representation” of women in forthcoming elections and other political and peace processes.[22] The missions in Mali, South Sudan, DRC, the Central African Republic (CAR), Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, and West Africa / Sahel all have cross-cutting mandates to implement WPS, including in the context of dialogue and women’s participation in political and reconciliation processes.

The inclusion of WPS in resolutions on peace operations stayed largely the same in terms of frequency and location within the resolution (i.e. operative paragraph, preambular paragraph, mandate), with the exception of resolutions on DPA-led missions, which were negatively impacted with the removal of a significant amount of information in the resolution on Afghanistan (see our analysis here or here).[21]

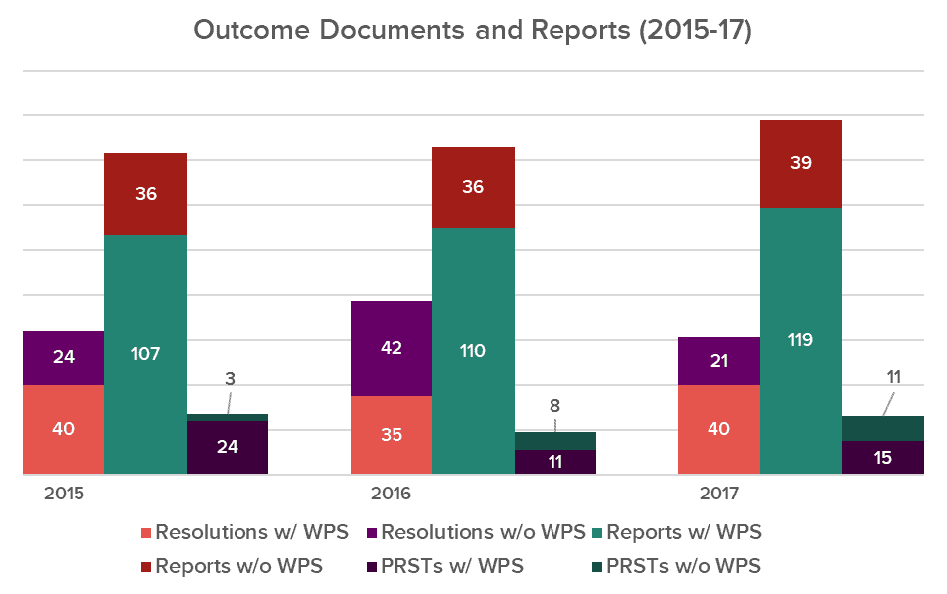

The following charts show the total number of outcome documents and reports that included at least one reference to WPS.

In 2017, the Council adopted two new provisions calling for gender mainstreaming across the work of two missions, Libya and Haiti, resulting in a total of ten missions mandated to mainstream gender as a cross-cutting issue. Gender was mainstreamed most effectively in the reports of the missions in Afghanistan, Libya, West Africa / Sahel, and the Great Lakes region, as evidenced by references to WPS occurring across multiple sections, in addition to a dedicated section focused on women’s rights and gender equality specifically.

There were four modifications and additions to the mandates of missions in terms of protection-related provisions in 2017:

- the mission in Sudan (Abyei) was asked to deploy a Women and Child Protection Advisor;

- the mission in DRC was asked to work with the government in addressing sexual violence at the strategic and operational level;

- the mission in Mali was explicitly asked to collaborate with women’s organization in its efforts to protect women and address SGBV;

- the missions in Somalia (UNSOM and AMISOM), were asked to work to protect women and girls from sexual violence, including SEA.[23]

Of the ten missions with mandates to protect civilians, only the peacekeeping operations in CAR, DRC, Mali, South Sudan and Sudan (Darfur) have a mandate which calls for specific efforts to protect women. Further, only six missions are specifically mandated to prevent and respond to SGBV, including as part of protection of civilians activities, as relevant.[24] Positively, new language calling on the mission in Mali to report on violations of women’s rights was added in 2017. Monitoring, reporting and addressing human rights violations, including SGBV was a mandated task for missions in seven countries; all of these missions are explicitly asked to include information on these violations in reports of the Secretary-General.[25]

New language was added to the mandate of the peacekeeping mission in CAR in 2017, requesting the mission implement gender-sensitive programs as part of overall DDR efforts; this new addition brings the number of missions mandated to ensure DDR efforts address the needs of women associated with armed groups to five out of 15 total peace operations mandated to undertake general DDR tasks.[26]

- For those missions mandated to address gender and DDR, only the reports of the Secretary-General on Mali and Colombia included information on related mission activities; the reporting on Colombia provided the most detail regarding developments in this respect, as well as analysis of barriers to reintegrating female ex-combatants. There was one particularly notable paragraph in a report on Colombia which detailed challenges facing pregnant ex-combatants; this is a positive addition, however, given this was the only reference to the particular health concerns facing former female combatants, it is essential that future reporting recognize that the health needs among ex-combatants should be taken into account. Additionally, other types of support to enable women’s full participation in reintegration activities should be mentioned along with the necessity of child-care facilities.”[27]

- In four reports on the missions in CAR, Sudan (Darfur), Somalia, and West Africa and the Sahel, some of the information provided was focused on the reintegration of girls or young people, although no information was provided regarding particular challenges facing girls or young women.[28] In the context of the West Africa and the Sahel, although the information in the reports of the Secretary-General on the regional political mission refer exclusively to the reintegration of the Chibok girls, other reporting on the region, including the Lake Chad Basin situation and CAAC in Nigeria, contains more detailed information on challenges faced by girls more broadly in the region and additional context for the provided statistics.[29] Ideally, this information would be consistent across reporting or at least cross-referenced and reinforced.

In 2017, the mission in Libya was given the mandate to ensure gender is mainstreamed throughout its mandate, including in SSR; this is a positive development due to the fact that prior to that point, only the missions in Mali, South Sudan, DRC, and Côte d’Ivoire, and Timor-Leste had similar mandates. For the most part, language calling on missions to address SSR was focused on institutional responses to SGBV. However, in recent years, the focus has shifted to include increasing women’s participation in the security sector, as evidenced in reports of the Secretary-General on CAR, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Afghanistan, and Guinea-Bissau.

- Regarding supporting gender-responsive security sector efforts, the reports on Côte d’Ivoire and Haiti all provided examples of how the missions were supporting efforts to ensure the security sector, including specifically the police, were trained to better address SGBV crimes.

- In the report of the Secretary-General on Liberia, there is an entire paragraph devoted to activities undertaken as part of efforts to build a gender-responsive security sector architecture; unfortunately, the paragraph primarily focuses on increasing women’s participation in the security sector, which is only one dimension of mainstreaming gender in SSR.[30] Externally, there have been institutional reviews of the peacekeeping mission’s success in SSR to determine the extent to which gender was mainstreamed; as such, it is unfortunate, that in one of its final reports, that aspect was neglected.[31]

The peacekeeping operations in Cyprus, Golan Heights and Western Sahara are considered “traditional” missions; that is, resolutions renewing the mandates of these missions contained only references to the importance of implementing the UN Secretary-General’s policy on sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by all personnel and do not include any WPS provisions in their mandates.[32] Positively, in the resolution focused on Western Sahara, one new preambular paragraph was added which called for women’s participation in the peace process; although this was only a preambular paragraph, given the extent to which the discussion on Western Sahara is entirely gender-blind, this is positive.[33]

Strategic Reviews

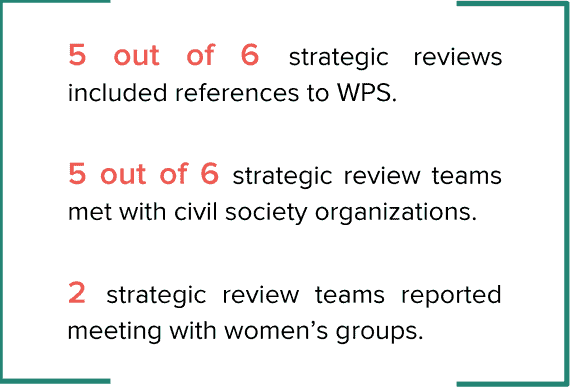

Strategic assessments are critical mechanisms in the cycle of mission planning which serve to evaluate the current mandate and determine staffing levels and operational priorities to ensure mission effectiveness. The reviews importantly inform the UN and Security Council ahead of the mandate renewal. In 2017, there were six strategic reviews conducted; five focused on the peacekeeping operations in Cyprus, DRC, Lebanon, Sudan (Darfur), Sudan (Abyei) and one on the political mission in Afghanistan.[34] The reports from all strategic reviews, except for Lebanon, referred to various aspects of the women, peace and security agenda.

- The highest frequency of references was in the reviews of the missions in Afghanistan and the DRC. These references generally focused on issues relating to SGBV, women’s participation in political and peace processes, and contextual information regarding the impact of the crisis on women.[35]

- Positively, there were substantive references to women in the review of the mission in Cyprus in the context of recommendations on strengthening the civil affairs functioning of the mission. The report noted that the review team had heard from several women’s groups that the mission could play an important role in ensuring “safe spaces” for civil society to meet in the context of community building.[36]

- Sexual and gender-based violence was the primary focus for the reviews of the missions in Sudan (Abyei) and Sudan (Darfur); both reviews noted that the issue was a particular priority, however, in both contexts, challenges in obtaining visas for staff and challenges regarding funding were identified as barriers in carrying out responsibilities related to human rights monitoring and reports, and some WPS activities.[37]

- The reports of all strategic reviews, with the exception of Lebanon, noted that the strategic review teams met with civil society organizations. However, only the reports on the reviews on Cyprus and DRC specifically noted meeting with women’s organizations.[38] This marks an improvement in overall consultations with civil society organizations (CSOs) during strategic review missions when compared to 2016.

Sanctions

In 2017, there were several positive developments on sanctions; with the establishment of the sanctions regime in Mali, a total of nine sanctions regimes include specific designation criteria that encompasses SGBV, and for the first time there was a call for gender expertise in the context of a country-specific sanctions regime. Although the overall proportion of associated experts group reports, which referenced WPS, only slightly improved compared to 2016, the quality of reporting improved in several country situations, albeit they were short references. In some cases only a sentence or two, they are significant considering the complete lack of attention to WPS less than two years ago. It is important to emphasize, however, that these references are often in separate sections focused on SGBV and are not mainstreamed throughout the report. The extensive conflict analysis that is often included in associated experts group reports is mostly gender-blind and overlooks the role of women and girls in armed groups, thus resulting in an incomplete picture of the dynamics of the situation.

Unfortunately, information sharing between the sanctions committees and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SRSG on SViC) decreased, with only one committee reporting a meeting with the SRSG, compared to three committees reporting meetings in 2016. Furthermore, most sanctions regimes continue to have mandates that are gender-blind and without concrete provisions calling for gender expertise within associated experts groups or reporting on WPS.

- The newly established sanctions regime focused on Mali positively includes targeting of civilians, including women and children, with violence (including rape or other sexual violence) as a designation criteria.[39] The Security Council also asked for the Panel of Experts to have gender expertise and both male and female members; it also requests that the SRSG on Sexual violence in conflict share information with the committee overseeing Mali sanctions.[40]

- The Security Council created separate designation criteria for individuals or entities who have carried out or planned acts involving SGBV in the Central African Republic; pulling it out of overarching designation criteria which involves a range of human rights violations.[41] Further, the resolution included more detailed language on SEA and called for perpetrators of SGBV to be excluded security forces.[42] Since the addition of this new criteria, the inclusion of information on SGBV in reports from the Panel of Experts has improved, including references to incidents of SGBV and some analysis of the way in which armed groups utilize SGBV to advance their ideology or goals. In contrast, there was little to no mention of SGBV in 2016 reports from the Panels of Experts. This improvement only underlines the positive correlation between sanctions regimes which include SGBV and/or targeting women as listing criteria and the inclusion of gender analysis in reporting: for instance, one report of the Panel of Experts (PoE) notes that armed groups are utilizing SGBV “as a tool for punishment or reprisal,” included additional details regarding the ways in which both men and women have been targeted, and noted one of the follow-up efforts undertaken by the government.[43] Positively, some of this information was also reflected in the reports of the Secretary-General on the peacekeeping mission in CAR; however, it is notable that it is the PoE reports which contained more analysis than the regular periodic reporting of the Secretary-General.[44] Unfortunately, despite the inclusion of this information in reports of the PoE, no individual or entity accused of SGBV was sanctioned last year.

- The Security Council added new language in the preambular paragraphs of the resolution renewing the sanctions regime in the Democratic Republic of the Congo but did not make any substantive changes to the designation criteria or mandate of the committee or PoE in 2017. Reporting from the Panel of Experts in 2017 also significantly improved compared to 2016; overall, there were more references to SGBV and the references were more detailed and analytical. For example, information regarding the demographics of particular women targeted, including their ages, as well as motivations behind the targeting of particular groups of women, were included in reports.[45] One of the reports also provided some gender analysis by noting that men were also targets of violence for failing to join the armed group and allowing women to escape captivity.[46]

- Only the committee overseeing the sanctions on South Sudan noted the SRSG briefed them on SViC; the committee also reported a similar briefing in 2016.[47] Reporting by the associated experts’ group was primarily the same concerning information and analysis of SGBV patterns and incidents, as compared to 2016.

- The sanctions regime for Libya does not include SGBV as designation criteria; a gap that should be rectified in future renewals. However, in 2017, reports by the associated experts’ group included references to women and gender for the first time. These references occurred in the context of discussions addressing trafficking and migration, and mirror the positive information and analysis that has been included in recent reports of the Secretary-General on migrant smuggling and trafficking of persons off the coast of Libya.[48]

Crisis Situations

In 2017, the Security Council adopted either resolutions and/or presidential statements on a range of country-specific or regional crisis situations. The Security Council’s response to country or region-specific crisis situations often includes the adoption of an outcome document to address either the emergence or recurrence of violence in a country or region which either does not have a peace operation or falls outside the regular cycle of decision-making on a peace operation.[49] The Security Council’s response to crisis situations also encompasses authorization of maritime interdiction in the course of countering piracy and addressing trafficking.[50]

Over the past four years, the Security Council has shown a marked improvement in its attention to WPS in crisis situations. Most significantly, in 2017, 93% of all decisions included a WPS reference, compared to 46% in 2016. This is particularly significant as it potentially signals an improved understanding by the Security Council that the WPS agenda is seen as relevant in all country-specific and regional deliberations.

Generally, in the context of outcome documents, the focus of the references was primarily a mix of women’s participation and addressing SGBV, with a slightly greater emphasis on women’s participation in the context of political, peace and security processes. Additionally, many of the references coupled women and children.

- Notably, for those countries which are the subject of repeated and ongoing attention by the Council, both over an extended period, but also in multiple contexts (i.e., crisis situation and peacekeeping operations – the Council tended to be better at addressing women, peace and security issues. Outcome documents adopted on situations in which there is also a peace operation included more robust calls for women’s participation and as well as more included balanced provisions regarding women’s rights. Further, although the Council does not adopt outcomes on the same countries every year, for those situations which were the subject of outcome documents in both 2016 and 2017 (Burundi, CAR, DRC, Somalia, South Sudan, West Africa / Sahel, and Yemen), all documents contained references to WPS, with the exception of the presidential statement (PRST) adopted in November 2017 on the DRC.

- The resolution adopted on the Lake Chad Basin region serves as an example of good practice in its inclusion of WPS language due to the breadth and scope of references on issues. References include discussions of ranging from gender inequality and root causes of conflict; the role of women’s organizations in conflict prevention and resolution efforts; protection and promotion of women’s rights; preventing and addressing SEA, as well as other forms of SGBV; and gender-sensitive approaches to countering violent extremism and DDR.[51] The Security Council’s consideration of Lake Chad Basin in 2017 is a positive example of how the different processes within the Security Council all integrated WPS and the gender analysis obtained throughout these informed the development of future considerations and outcomes. The IEG met ahead of a Security Council mission to the region. Following this, the Security Council mission had strong women, peace and security elements in its Terms of Reference. As a result, Council members met with local women and women’s organizations multiple times, including in internally displaced person camp in Maiduguri, to hear directly their recommendations and concerns. This Security Council mission should be considered as best practice on how to integrate WPS for future Council missions, as it also resulted in the adoption of Security Council Resolution 2349 (2017) which included among other WPS references the importance of dialogue with civil society including from women’s organizations; the need for a holistic approach to defeat Boko Haram and ISIL/Da’esh, which includes ensuring women’s participation and empowerment, the need to address root causes to a conflict, including gender inequality. One of the civil society representatives whom the Council met with while in Nigeria was also subsequently invited to provide an update to the Council later in the year.

- Importantly, there was only one country-specific PRST without WPS language in 2017; that PRST was focused on sanctions and the investigation of the killings of the members of the group of experts in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[52] In addition to the PRST, within reporting of the Secretary-General on the elections in the DRC, there have also been few to no references to WPS.[53] This gender-blindness is incongruent with the Council’s broader discussions on the situation in the DRC which, although slightly skewed towards addressing SGBV, does refer to WPS issues across resolutions and reports. Reports of the Secretary-General on the elections failed to provide any further information or analysis on efforts to engage women or ensure women’s access to and participation in the elections. The failure to include even basic references to women’s participation in the elections is unfortunate given the periodically robust accounting in reports of the Special Envoy on the Great Lakes on women’s participation in various political processes in the region.[54]

- The Security Council continued to ignore the gender dimensions of the crisis in Syria across all outcome documents, with reports of the Secretary-General similarly devoid of substantive discussion of the impact of the ongoing crisis on women and girls.[55] References in the two resolutions adopted in 2017 can generally be characterized as broadly acknowledging how women and children, as civilians, are impacted by the humanitarian crisis and violations of human rights.[56] Reports of the Secretary-General continue this trend, with only 30% all references to women, substantive in nature.[57] The majority of references were statistical details regarding the beneficiaries of humanitarian programs or activities; most of these statistics were disaggregated by sex. The substantive references were primarily focused on ways in which the Special Envoy engaged with women, specifically the Syrian Women’s Advisory Board, in the peace process; however, although there was reference to engagement with women’s groups, there was rarely any follow-up information or detail on the impact of this engagement or the substance of the engagement in the long-term.[58]

- Positively, the PRST on the situation in Burundi, adopted in August 2017, included references to WPS across the spectrum of the WPS agenda.[59] There were multiple calls for particular attention to and support for women decision-making and political dialogue processes, as well as language condemning violence targeting women, including a reference to the forced impregnation of women and girls, in the context of efforts to incite violence and hatred.[60] Additionally, the PRST also included a reference to supporting women’s groups.[61] However, the report on Burundi was focused primarily on human rights violations, failing to include substantive information on the participation of women in the political process in order to reflect calls made by the Council in previous outcome documents.[62]

- The PRST adopted on the situation in Yemen in June 2017 included one paragraph on the importance of women’s participation in peace negotiations and notably, called for 30% representation of women and regular reporting on consultations with women’s leaders and organizations, under resolution 2122 (2013).[63] As a follow-up, the outcome of the November 2017 IEG meeting noted that the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSE-Yemen) was looking for alternative ways of engaging women, including specifically the Yemeni Women’s Pact for Peace and Security, which meets regularly with Special Envoy’s office, in the peace talks, given that neither party complied with the quota.[64] The discussion of the quota in the IEG meeting, following from the PRST, is an excellent example of the sort of follow-up that the IEG is meant to engender. Particularly for a situation like Yemen, in which there is no periodic reporting of the Secretary-General, the flow of information through the IEG is that much more important.

- The Security Council renewed its authorization of maritime interdiction in the context of countering piracy off the coast of Somalia and smuggling of migrants and trafficking of persons in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of Libya.[65] The two resolutions maintained the same WPS references as contained in the 2016 resolutions.[66] Reporting of the Secretary-General on piracy off the coast of Somalia technically improved compared to 2016, with the inclusion of one reference to WPS in the list of priority areas within a new framework of cooperation between the UN and African island States.[67] However, a lack of additional information or analysis of the gender dimensions of piracy calls into question the degree to which the issue is a priority.[68] Reporting on smuggling of migrants and trafficking of persons off the coast of Libya has historically contained multiple WPS references, typically focused on the human rights violations, as well as details regarding rescue or intercepting interventions and efforts to intercept or rescue them. Notably, these reports also used the standard phrasing of “women, men, girls, and boys” when referring to the human rights impact on individuals who are trafficked; although the details regarding the gender-specific ways they are impacted are not included, the recognition of the impact on men and boys is vital in moving towards a gender analysis of the situation.[69]

Thematic Issues

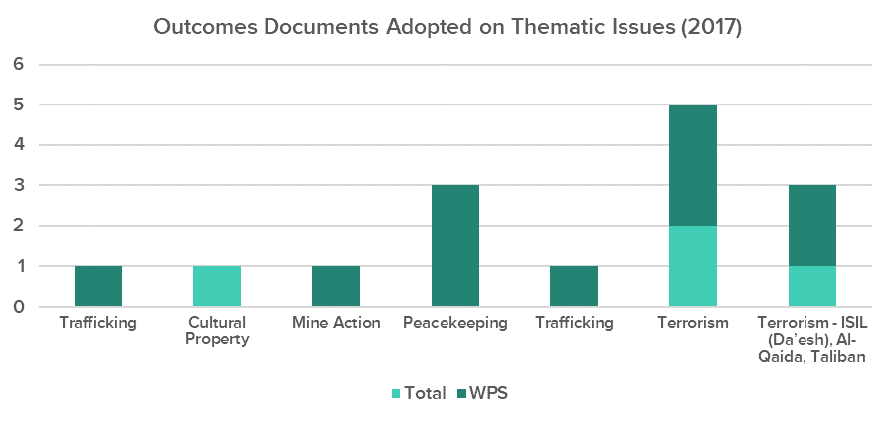

In 2017, the Security Council discussed 12 thematic issues by adopting outcome documents or considering reports of the Secretary-General or relevant subsidiary bodies. Resolutions and PRSTs were adopted on six thematic agenda items; all but one resolution included reference to WPS. All thematic reports included a WPS reference.

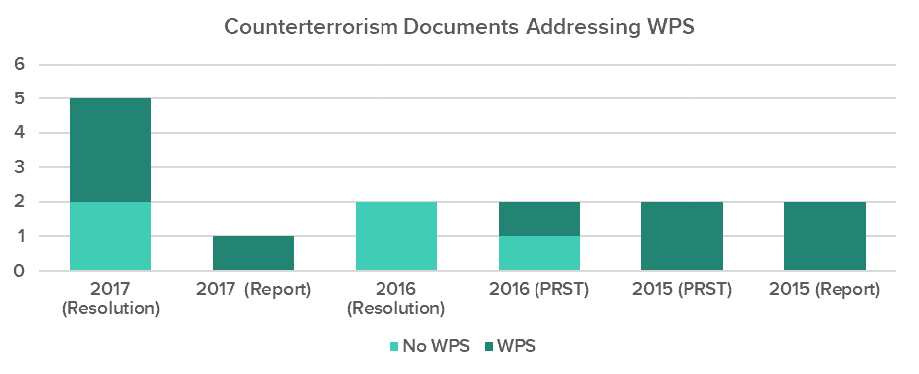

Due to the fact that the Security Council does not adopt resolutions or consider reports on the same thematic issues every year, it is difficult to compare presence and consistency of WPS references year- by- year. It is possible to compare the three thematic issues of peacekeeping, trafficking, and counter-terrorism, in which the Security Council either maintained or improved its attention to WPS. Most significantly, in the context of issues related to countering terrorism and violent extremism, the Security Council significantly improved its references to WPS, due in part to its renewal of the mandate of the Counter-terrorism Executive Directorate (CTED), which included new mandate provisions on WPS. Although outcome documents often failed to include substantial references to WPS; reports of the Secretary-General had some few, positive inclusions, most notably in the reports on protection of civilians and SALW.

Over the last three years, on most thematic issues, there have been references to WPS in either outcome documents or reports of the Secretary-General.

- Overall, attention to girls, in the context of CAAC improved in 2017, however, the improvements were broad. References to the particular challenges faced by girls or the need to ensure that interventions and assistance meet the needs of girls remained scarce, with the few references primarily focusing on patterns or incidents of sexual violence targeting girls. The thematic report of the Secretary-General included several references to particular targeting of girls in specific country situations, as well as statistical information on violence targeting girls; notably, the report also contained a few recommendations which emphasized the importance of addressing the particular concerns of girls, including in the context of reintegration, which mirrors the positive reference in the thematic PRST.[70] The PRST adopted at the end of an open debate discussing the Secretary-General’s report made two specific references to the particular targeting of girls in the context of sexual slavery, as well as recognition of the importance of ensuring that the specific needs of girls are met in reintegration processes, reflecting the recommendations from the report.[71]

- The Security Council Working Group on CAAC adopted conclusions on Colombia, Nigeria, Philippines, Somalia, and Sudan.[72] Additionally, a report of the Secretary-General on the situation of children in armed conflict in Myanmar was also submitted to the Security Council.[73] All reports and all conclusions, except those focused on the Philippines, referenced girls.[74] There was an inconsistency between reporting and conclusions; for example, there was no information on reintegration of girls in the report of the Secretary-General on CAAC and Sudan, but the conclusions included a recommendation.[75] Conversely, most references in the report of the Secretary-General on CAAC and Sudan referred to SGBV targeting girls; however, there were no recommendations to that effect. Overall, very few references were solely focused on discussing the challenges faced by girls; the exception was the report on Nigeria which included several notable references to the particular challenges facing girls. The attention to the situation of girls was reflected in the resolution adopted by the Security Council on the Lake Chad Basin region in March 2017.

- In June 2017, the Security Council adopted the first, stand-alone resolution on mine action; positively, the resolution included a reference to the need to take into account gender and age-specific considerations in the context of mine action.[76] Further, the Security Council referred to the role and presence of civil society, recognizing the importance and need for stakeholders, international actors, and CSOs to assist with landmine clearing initiatives; this language is an improvement from previous mine action GA Resolutions which did not contain any WPS references.[77]

- Under the thematic agenda item of peacekeeping, the Council adopted several outcome documents in 2017, two resolutions and one PRST, all of which referenced the WPS agenda.[78] References primarily focused on the role of women in peacekeeping and peacebuilding processes, including as police, the importance of gender expertise in peacekeeping missions, and preventing and addressing SEA.[79] In contrast, thematic resolutions focused on peacekeeping adopted in 2016 included a more extensive range of references to WPS, including the role of women’s groups and women’s leadership in conflict prevention and resolutions, and calling for more resourcing.[80]

- In 2017, the Security Council adopted one resolution and received one report of the Secretary-General on the thematic agenda item of trafficking; both included several references to WPS, primarily with a focus on the way in which trafficking particularly impacts women; acknowledging the various human rights violations associated with trafficking, including SGBV; and the need for appropriate care, assistance, and service to survivors.[81] One noticeable gap in the context of the report of the Secretary-General is a lack of gender analysis on how trafficking is often exacerbated by foreign military presence and proliferation of arms. Although the report acknowledges the link between SEA and trafficking, there is a need for sharper and more inclusive analysis on the way in which military bases provide a steady market for women, girls, and boys who are forced into sex work due to poverty or trafficking, as well as the need for accountability of state actors, including border control and military actors in contrast to non-state actors.[82]

- The Security Council considered one report of the Secretary-General on the issue of SALW; similar to the most recent previous report from 2015; the report contained a few, particularly strong references to the WPS agenda.[83] Specifically, the report discussed the role of SALW in facilitating SGBV, including intimate partner violence and the link between conceptions of masculinity and the proliferation of SALW.[84] Compared to the last report of the Secretary-General, published in 2015, there was a decrease in the frequency and complexity of the references to the WPS agenda. For example, the 2015 report acknowledged women’s role as users of SALW, combatants, and armed traffickers, rather than solely as victims of gun violence, and further re-emphasized the importance of women’s participation in planning and implementing efforts to combat the proliferation of SALW, pursuant to resolutions (SALW SCRs), 2122 (2013) and 2242 (2015).[85]

- References to WPS broadly included calling for women’s participation in countering violent extremism, including countering narratives, and gender-sensitive approaches in terrorism-related investigations. There remains a disconnect between the resolution’s call for integration of gender as a cross-cutting issue and reporting. While the Security Council includes numerous references to women’s rights, gender, and civil society in the reporting, the majority of references are mainly descriptive and do not unpack the impact of terrorism and counter-terrorism activities on women and girls.The Security Council discussed issues relating to counter-terrorism under both a general, thematic agenda item and in the context of sanctions aimed at specific extremist groups. Historically, the Security Council has been weak in addressing WPS in the context of the thematic issue of counter-terrorism. However, in 2017, the Security Council adopted 5 resolutions and considered one report of the Secretary-General on the thematic agenda item of counter-terrorism; 67% of all documents included references to WPS, reflecting language adopted in resolution 2242 (2015).[86] Over the last three years, the Council has progressively gotten better at including WPS; however, there is still a long way to go.

- Notably, in its renewal of the CTED mandate, the Council integrated gender and women’s human rights promotion and protection as a cross-cutting issue throughout CTED’s activities, in addition to including previously agreed language from resolution 2242 (2015) on gender-sensitive research and data collection on radicalization of women and the “impact of counter-terrorism strategies on women’s human rights and women’s organizations.”[87] The report on CTED’s activities over the course of 2017 dedicated a section to gender as a cross-cutting issue in activities and noted it conducted gender-sensitive research on both these topics. However, there was no further detail regarding the findings of this research or how it this will influence activities moving forward.

- The Security Council adopted two resolutions, one PRST, and considered seven reports under the agenda item focused on Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL/Da’esh); although both resolutions referenced WPS, the PRST and several reports of the Secretary-General failed to address WPS concerns. The Council adopted resolution 2379 (2017) which set up an investigative team responsible for collecting, storing, and preserving evidence of crimes committed by the group in Iraq; Positively, resolution 2242 (2015) was referenced. However, there was no reference to women’s and civil society participation (only regional and intergovernmental organizations).

- The bulk of the focus, in terms of WPS, were violations of women’s rights and victimization of women by terrorist groups. Despite the improvements in the context of the thematic issue of counter-terrorism, references to women’s rights and gender in the discussion of ISIL/Da’esh are mostly anecdotal with a focus on violence perpetrated against women by terrorists, including sexual violence and trafficking. Further, to date, no member of Da’esh has been held accountable for SGBV.

Missed Opportunities

There has been a lot of progress at the normative level in advancing the WPS agenda. Yet, gaps remain in the Council’s approach to WPS both regarding specific thematic issues, as well as lack of attention to intersectional and diverse voices and concerns, which prevent nuanced, holistic implementation of the WPS agenda.

Gender-responsive humanitarian action

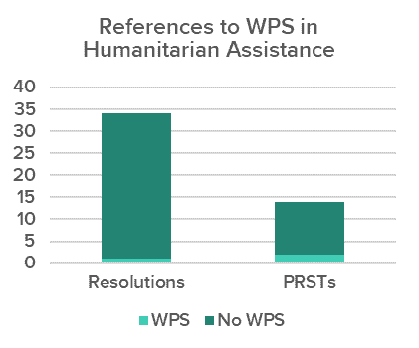

The Security Council addresses humanitarian assistance in most country-specific and regional situations on its agenda including by mandating peace operations support and ensure access for humanitarian providers. However, despite widespread discussion on the issue; the topic remains almost entirely gender-blind.

In 2017, 47 outcome documents referenced humanitarian assistance; only three of these, one resolution on the Lake Chad Basin region, and two PRSTs on Burundi and Myanmar, included a reference to women or gender.[88] To date, the resolution on the Lake Chad Basin region contains the most active language from the Security Council calling for gender-sensitive humanitarian efforts outside of thematic resolutions.

Reporting on humanitarian assistance is similarly gender-blind; only ten reports contained references outside of the provision of sex-disaggregated data. References to WPS in reports generally focus on the presence of resources and programs for survivors of SEA, on occasion including information on SGBV initiatives, training, and workshops conducted on the local and national levels.[89] References to women and/or gender and humanitarian assistance were largely concentrated in reporting on the situations in Somalia, South Sudan, Iraq and the Lake Chad Basin region (including the report of the Security Council field mission). Interestingly, while reporting on gender-sensitive humanitarian assistance was scarce, specific reports contained suggestions on enhancing humanitarian assistance in the recommendation and observation sections.[90] Generally, this type of disparity often indicates the influence of individuals in the report drafting and finalization process; rather than the effectiveness of internal gender mainstreaming.

A lack of gender-responsive humanitarian assistance contributes to ineffective, unsustainable assistance programs that fail to meet the needs of the most impacted communities in a conflict setting, namely women and girls. Oftentimes, a lack of gender-responsive humanitarian assistance can exacerbate existing inequalities that further entrench harmful gender dynamics. Integrating gender-sensitive tools and programming into humanitarian responses should no longer be viewed as an optional luxury but rather as a strategic necessity, to meet the needs of women and adolescent girls, including individuals with disabilities.

Addressing the concerns of women and girls formerly associated with fighting forces and ensuring gender-sensitive DDR processes

The Security Council has historically been inconsistent in recognizing the importance of addressing the specific needs of women and the specific needs of girls currently or formerly associated with armed groups. In 2017, the Security Council referred to DDR in several resolutions; only five of those resolutions contained WPS references in the context of the DDR processes.[91] Similarly, reports of the Secretary-General fail to provide substantial information, even in the context of country situations in which there are calls for gender-sensitive DDR processes and the participation and leadership of women and girls in DDR/R processes. In other instances, despite the clear gender dimensions of the DDR process, the Security Council completely overlooks this issue.[92] For example, in Colombia, despite the fact that women make up 23 percent of former FARC-EP members who demobilized, according to the national census, the Security Council references neither DDR processes nor the participation of women in this regard.[93] In 2017, the Secretary-General’s reports included information on DDR processes in their reporting on CAR, Côte d’Ivoire, Central Africa, Mali, South Sudan, and Sudan.[94] General references to DDR processes focused on challenges to driving forward DDR processes, the participation of armed groups in DDR processes, the disarmament of ex-combatants, progress on initiatives and projects, and UN and national DDR strategies.[95] References to gender-sensitive DDR were discussed in reports on CAR, Colombia and Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, and Mali concerning the participation of female ex-combatants in DDR and repatriation programmes.[96]

However, typically references lacked attention to the gender dimensions of DDR processes and did not include information on the participation and leadership of women and women’s groups. References also failed to address the stigma or social exclusion that surrounds women and girls in the process of reintegration which prevents them from participating in the country’s social, political and economic life, accessing services and opportunities, and further interferes with participation in DDR programmes.[97]

Intersectionality in the women, peace and security agenda

The Security Council and Secretary-General have still yet to make a genuinely comprehensive WPS agenda in outcome documents and reports, respectively. There are still many missed opportunities to address the root causes of conflict, including gender inequalities, marginalization of minority groups, militarized masculinities and discriminatory power structures that marginalize women’s participation and consequently hinder conflict prevention and resolution.

In the majority of outcome documents adopted by the Security Council, and throughout reports of the Secretary-General, women and girls are primarily referred to as a monolithic group, without any reference or acknowledgment of unique challenges particular groups of women face in conflict-affected situations, such as women and girls with disabilities, indigenous women, individuals with diverse SOGIESC or older women. This failure to include substantive references to the age-differentiated experiences and needs of girls, adolescent girls, young women, and older women as well as the multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination and violence experienced by women and individuals with diverse SOGIESC in conflict-affected situations reinforces the severe implications of deep-rooted intersectional inequalities sustainable peace.

Mainstreaming gender and addressing masculinities

“Women” and “gender” are often used interchangeably in peace and security discussions of the Security Council; in fact, nearly all instances in which the term gender is used in resolutions, PRSTs, and reports of the Secretary-General, are followed by a reference to women.

In the context of the work of the Security Council, there is little to no awareness or discussion of the way in which violent masculinities are perpetuated, and discussion on “men” as gendered beings is also rare. In resolutions and reports, “men” are rarely explicitly mentioned; when men are explicitly mentioned as a social category, it is usually in the context of acts of violence, including SGBV. This is problematic because it reduces men to one aspect of masculinity and focuses on men as the aggressors; this problematization is similar to the earlier discussion on women being reduced to victims/civilians needing protection, which strips them of their agency and fails to recognize that women can be aggressors, perpetrators, or active participants in anything, the persistent and exclusive characterization of men as aggressors plays to a variety of roles in peace and security, as well as in conflict, that results in the perpetuation of violent masculinities. The lack of a broader gender perspective, including masculinities, in WPS policies, contributes to instrumentalist implementation approaches, with a predominant focus on women as victims or ‘add-ons,’ without linking this to a broader picture. In the context of reporting of the Security Council, for example, “armed men” comprised close to 30% of the references. Additional terms used include “men with weapons,” “men in uniform,” “Arab men,” and “armed tribesmen.”

Prevalent language paints a picture of conflict as something that is created by men (cause), and that happens to women (impact) – which fails to address the impact of conflict on men and the active roles that women can play in post-war societies. The references to men in non-combatant roles, outside of sex-disaggregated data, are few and far between and limited to reports on Afghanistan, Libya, Cyprus (Special Envoy), Iraq, and DRC (Sanctions Group). It is notable that except for DRC, those are political missions. Two references made a note of the pressure facing men who refused to join armed groups, listing loss of jobs, closure of businesses, restrictions on movement, and targeting for SGBV, as examples of repercussions.[98]

Working on masculinities is going beyond ‘working with men’; instead, it is about changing patriarchal mindsets and addressing the need for structural and institutional change. Further, failing to engage in a holistic conception of gender also results in an incomplete understanding of the root causes of gender inequality, and armed conflict.

Given that men and boys comprise the majority of combatants and military leaders, it is essential to understand how patriarchal gender norms and masculinities contribute to violence, insecurity, and conflict.[99] Research has shown that “gender roles, and patriarchal notions of masculinity, in particular, can fuel conflict and insecurity, motivating men to participate in violence and women to support them or even pressure them to do so.”[100] Further, recruitment of combatants can also be through valorization of violent masculinities and by underlining how taking on a fighting role is “being a man,” or necessary to earn an income or be the “protector.” Privileged and mostly violent forms of masculinity exist on all sides of a conflict and can influence both the conduct of the fighting itself as well as the decisions that are made in conflict resolution.

Failure to genuinely mainstream gender and take into account masculinities also indicates that efforts to address gender equality are superficial. At the heart of gender inequality are “patriarchal gender norms,” which can contribute to violence and conflict, particularly in situations where “militarized notions of masculinity are prevalent.”[101] The “cultures of militarized masculinities,” combined with militaristic attitudes and behaviors, “create and sustain political decision-making where resorting to the use of force becomes a normalized mode for dispute resolution” thereby perpetuating conflict and violence.[102]

Sexual and gender minorities

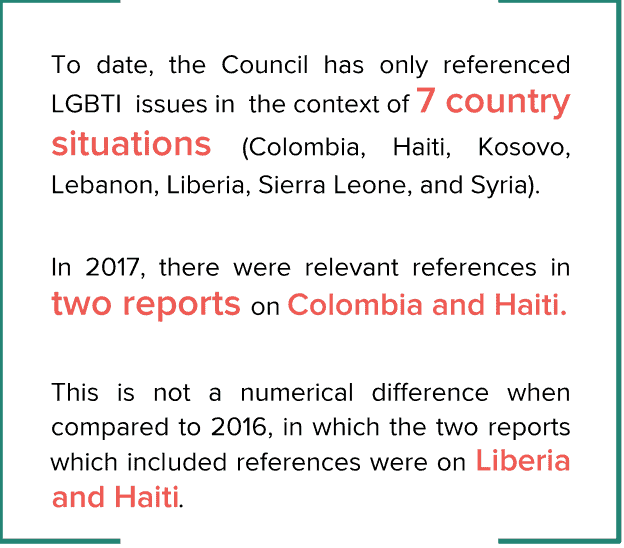

Consideration for the rights, concerns, and experiences of individuals with diverse SOGIESC have been mainly absent from the Security Council’s discussions on peace and security; references only tend to occur in reports of the Secretary-General on specific country or thematic issues, and to date the Security Council has failed to adopt any outcome document referencing SOGIESC.

Given the particular risk facing individuals with diverse SOGIESC, there is a necessity to take this into account in the context of any conflict analysis or efforts to protect and promote human rights.[103]

Over the past several years, references occurred in reports of the Secretary-General on Lebanon, Sierra Leone, Kosovo, Haiti, and Syria, primarily in the context of specific activities undertaken by the vital mission on efforts supporting the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people.[104] The report on the UN mission in Sierra Leone, which closed its doors in 2013, is particularly notable, as it provides details on the mission’s efforts to protect LGBTI individuals, as well as similar efforts within the community and even contained a separate section on its activities.[105]

Beyond country-specific reports, thematic reports on women, peace and security and conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) have mentioned related issues. The 2015 report of the Secretary-General on CRSV noted that new information on individuals targeted “on the basis of their (actual or perceived) sexual orientation has come to light as a form of social control employed by certain armed groups in the Syrian Arab Republic, Iraq and elsewhere.”[106] Further, the report notes that sexual violence, in particular, is being carried out “as a form of “corrective violence” or to “cleanse the population,” which has caused many to flee areas under the influence of armed groups.”[107]

In 2017, two reports referenced LGBTI persons focused on the situation in Colombia and Haiti. In the context of the situation in Colombia, the report noted that LGBTI issues – which will be included in the broader gender perspective – are supposed to be mainstreamed as part of the peace process. The UN’s engagement in Haiti included partnering with the LGBTI community. In fact, in the final report on MINUSTAH, the Secretary-General noted that the mission “highlighted human rights concerns with respect to draft laws on good moral conduct and marriage, adopted by the Senate on 30 June and 1 August, the provisions of which appeared to target LGBTI people and other minority communities.”[108]

Subsequently, the new ROL mission in Haiti, MINUJUSTH, includes an indicator in its results based budget framework, that calls for the adoption of measures to protect vulnerable groups against discrimination, including LGBTI persons; this is one of the first indicators of achievement that includes language related to LGBTI persons for a peacekeeping mission.[109]

Civil Society and Human Rights Defenders

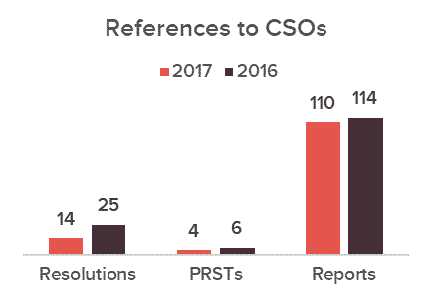

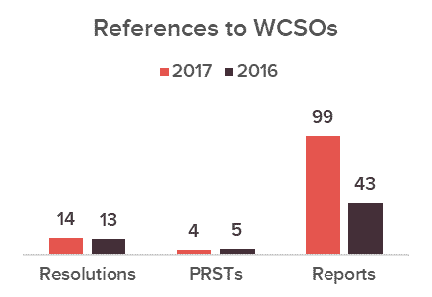

The substantive inclusion of references to CSOs did not change between 2017 and 2016; notwithstanding, references to human rights defenders (HRDs) declined.

Civil society, women’s organizations, women’s rights activists and the WPS agenda are inextricably linked, both in origin and implementation in the work of the Security Council. In thematic resolutions and PRSTs on WPS adopted over the last 16 years, the Security Council has reinforced, acknowledged, and highlighted the role of civil society more than 40 times, calling for Member States and the UN to work with civil society in conflict prevention efforts, peacebuilding, provision of humanitarian assistance and peace processes.[110]

CSOs have been recognized as crucial interlocutors in conflict situations, contributors to early warning and conflict prevention efforts, and, at times, more effective than international actors in settling local disputes and providing humanitarian and development assistance. There has been an overall increase in references to the role of civil society in resolutions adopted by the Security Council since 2000. Although not always referenced in the context of WPS, some of the earliest references to CSOs in Security Council resolutions were in country-specific resolutions on Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2002, in which the Security Council recognized and encouraged the ongoing contribution of the Mano River Union Women’s Peace Network to regional peace.[111]

Currently, ten peacekeeping operations have specific tasks mandating collaboration with or support of CSOs, women’s groups, and/or HRDs.[112] The mandate for the mission in South Sudan is the most comprehensive, calling on the mission to engage with CSOs, including women’s groups and HRDs, on different activities.[113] The missions in Mali, CAR, Somalia, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and the regional office for West Africa and the Sahel explicitly requested to collaborate with women’s organizations and women civil society leaders and/or CSOs in order to achieve WPS-related tasks in the context of protection of civilians; human rights monitoring; good offices; implementation of peace agreements; and DDR activities.[114]

Outside of peace operation mandates, references to civil society, including women’s groups, generally fell into several categories: recognition of the importance of civil society in peace and political processes; condemnation of harassment and intimidation of CSOs and HRDs; and calls for support and inclusion of civil society in various processes.